Let's organize a better economic system

This blog post will spin off from four sources: 1. https://fab.city/ “The transition towards productive and regenerative economies in regions and cities, driven by people.” 2. Economic Governance Roadmap for the Fab City Economy on FCOS (FCOS = FabCity Operating System) 3. Valueflows and FCOS 4. Mentioned in #2 (“For a guide in terms of power distribution within institutions/networks, we use institutional economics (see Elinor Ostrom , a prominent scholar of the commons”)). One of the main ideas of Institutional Economics is that economics is “the science of social provisioning”'.

Fab City is an economic network

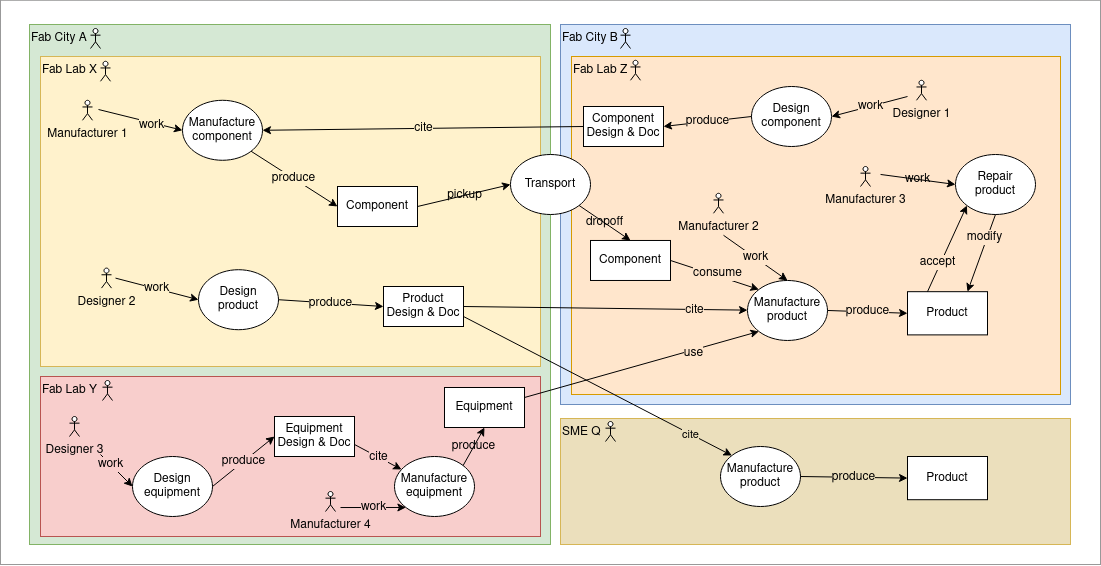

The network is composed of several institutions. We'll focus here on FabLabs that design and manufacture goods, and FabCities, where the FabLabs live, and are helped and somewhat governed by FabCity organizations.

What makes these into an economic network rather than separate institutions is their economic relationships, where Economic Agents (the FabLabs, their members, and their related organizations) collaborate in Economic Processes that create, transport, and transfer Economic Resources between them.

FabLab networks might become supply chains

...where (for example) one FabLab designs a component that is then produced in another FabLab and then assembled into a product by another FabLab. You can see many of those relationships in the resource flow diagram above.

If they collaborate in those ways a lot, they will start to strengthen their relationships. Here are three stages of development of supply chain relationships, each stronger than the previous stage.

- Transaction Integration “Level one involves computerization of general business activities and transactions.” FabCity can reach that level by implementing Valueflows networks.

- Information Sharing Designs, agreements, etc, can also be shared via Valueflows networks.

- Strategic Collaboration “...you and your supply chain partners will be collaborating on planning and redesign processes, and you will usually be sharing some risk and reward” (which of course can also be shared via Valueflows...)

...and beyond those three... 4. Partial or complete economic and/or physical integration Apple is one of the companies that invests a lot of money into their suppliers, for example, Apple invests 410 million into one of its optical tech suppliers. Ford has also done some partial integration where suppliers set up sub-assembly-lines within their main factory.

For each of those levels of integration beyond the first, the supply chain partners are no longer dealing with each other by market relations based on prices alone. And even the first level, transaction integration, usually requires some technical collaboration and probably some contractual agreements.

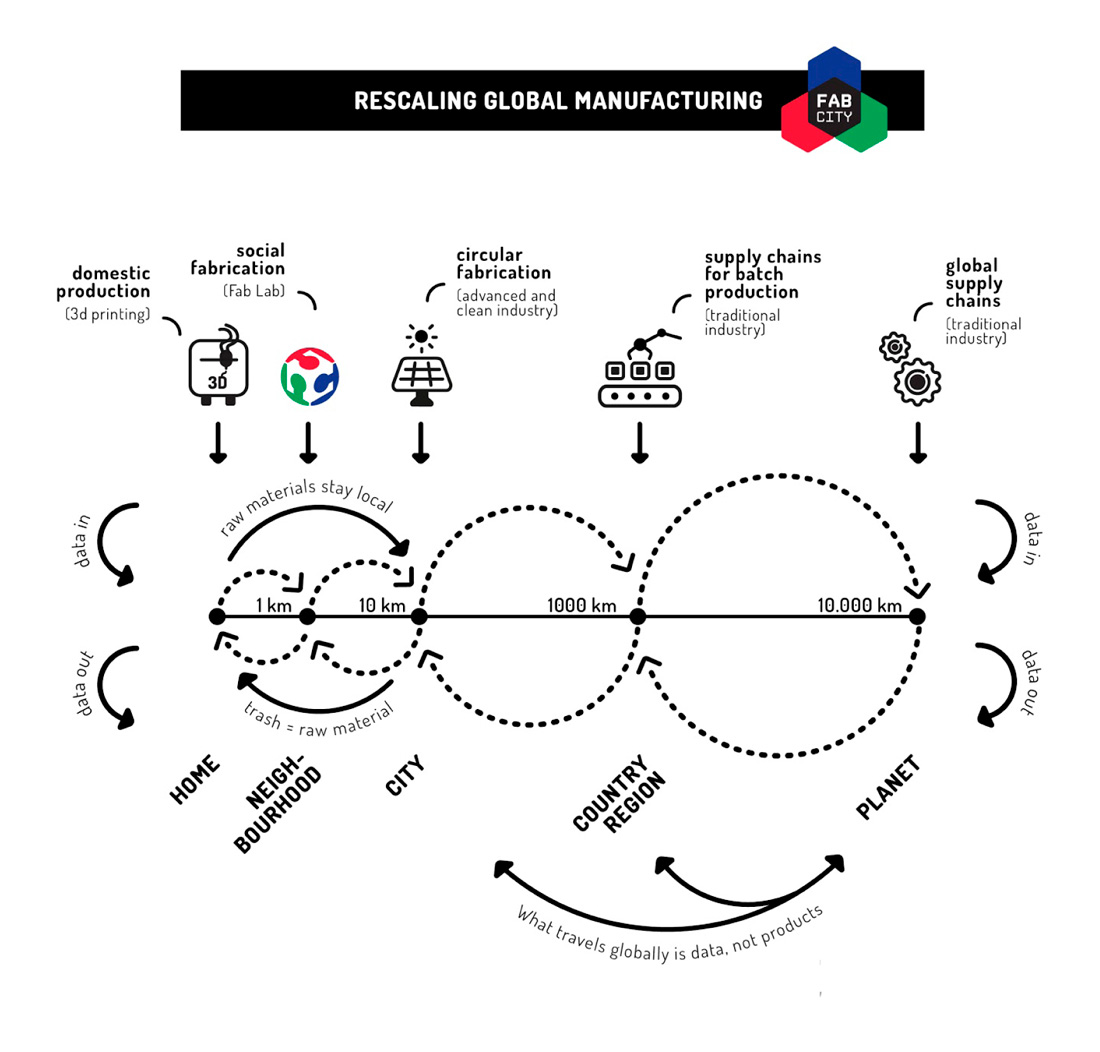

From Product-in-Trash-Out to Data-in-Data-out

The circular economy principles of FabCity are yet another level, beyond supply chain integration, on to community governance agreements.

Institutional Economics

Elinor Ostrom

She was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics, for among other research, Design principles for Common Pool Resource (CPR) institutions, and also, Ostrom's Law:

Ostrom's law is an adage that represents how Elinor Ostrom's works in economics challenge previous theoretical frameworks and assumptions about property, especially the commons. Ostrom's detailed analyses of functional examples of the commons create an alternative view of the arrangement of resources that are both practically and theoretically possible. This eponymous law is stated succinctly by Lee Anne Fennell as:

A resource arrangement that works in practice can work in theory.

Ostrom studied economic institutions in real life. One of her most important findings was how community institutions can and often do manage the theoretical “Tragedy of the Commons”.

Heterodox Economics

Institutional economists often call themselves “Heterodox Economists”. to differentiate themselves from “orthodox economists”, as in the article below about social provisioning.

Social provisioning

Note: this section is incomplete. Needs more research into social provisioning, to come soon.

The Social Provisioning Process and Heterodox Economics

'The social provisioning process is how heterodox economists define economics in general. Instead of having a narrow definition of what constitutes economics, such as the mainstream has with its allocation of scarce resources among competing ends via the price mechanism, heterodox economists have opted for a much more expansive definition that permits different theoretical explanations for ways in which the provisioning process can take place in different types of economies in different historical contexts. In this chapter, we first examine the changes in the definition of economics from classical political economy to neoclassical and heterodox economics. The comparison between classical political economy and neoclassical economics manifests a clear distinction in view of economy and economics. The second section substantiates the meaning of the social provisioning process. In doing so we make a case that, first, defining heterodox economics as the study of the social provisioning process positions heterodox economics as an alternative to neoclassical economics, and, second, that such an expansive definition of economics has potential to synthesize various heterodox theoretical frameworks in a constructive manner. “ -Tae-Hee Jo

(I won't get deep into that paper in this blog post. but it's really good...instead, I'll focus on what they mean by social provisioning.)

“Essentially, individual units of economic activities are embedded in the economy, which is in turn embedded in and an integral part of the society in particular regard to the material basis of the society. In this perspective, nothing is isolated from and independent of the society. It is interactive agency through social institutions that renders individuals, organizations, and the whole society on-going. It follows that an analytical reduction of the whole to the individual or the converse is neither possible nor sensible, since such an attempt expunges all the interrelationships between constituents that generate, constrain, or facilitate the dynamics of the social system. By the same token, it is inconceivable that an economy is viewed as a system of exchange organized by the market price mechanism, which is at odds with empirical reality and which is theoretically incoherent.” -Tae-Hee Jo

Another angle on social provisioning that leads right back to FabCity is the circular production economy:

“In this production-oriented, production-based capitalist system, resources are reproduced in the technically interrelated process of production between capitals or industries—that is, the circular production economy, which is most rigorously and clearly formulated by Sraffa (1960).

“The circular production economy indicates that production is not only a complicated process which can hardly be represented by a simple neoclassical production function, but also a social process in which basic goods and the surplus goods sectors are technically connected, and going concerns—households, the business enterprise, the state, and market governance organizations—are socially connected to each other through the structure of production and incomes. In this theoretical framework, the viability of the system as a whole (and of going concerns therein) becomes a fundamental question, as opposed to the feasibility of production based upon scarce resources and the efficient allocation of resources through the market mechanism.” -Tae-Hee Jo

As rendered by FabCity:

Critical comment

The Methodology and Guiding Principles section of Economic Governance Roadmap for the Fab City Economy on FCOS says, “To argue for a certain order of the economy that shall unfold itself on top of FCOS, we set guiding principles, also with the help of economic theory. For economic governance, we utilise transaction cost economics. For a guide in terms of power distribution within institutions/networks, we use institutional economics (see Elinor Ostroms , a prominent scholar of the commons). For the price mechanism, we choose microeconomics. [...] “For the price mechanism, we analyse marginal costs, which are the costs that arise when producing an additional unit of a given asset/artefact/product. “

From the explanations of institutional economics cited above, it should be clear that institutionalists contradict marginal costs and similar price mechanisms. In fact, one of the well-known institutionalist papers is entitled “Redefining economics: from market allocation to social provisioning”.

Institutional economists would observe and analyze the economic networks of FabCity and very probably (as suggested in the Strategic Collaboration level of supply chain integration) share some risks and rewards, for example, rewarding designers even though marginal cost theory might say otherwise.

Likewise, the overall goals and network designs of FabCity are very consistent with institutional economics, with their circular glocal economy principles, while microeconomics would advise self-interested agents who pass their externalities off to their communities (the indivisible foot accompanying the invisible hand).

But enough theory, what to do in real life

To come...