The Importance of Being Authorised

Getting a practising certificate might be an annual ritual for most lawyers in law firms in Singapore. Still, a recent case — Choo Cheng Tong Wilfred v Phua Swee Khiang — reminds us of its critical significance in our legal industry.

Suffice to say, because the lawyer did not have a practising certificate, he was not authorised to practice law in Singapore. Because he was not authorised, he was not entitled to any fees for legal work performed.

This rarely comes up because lawyers here must be in law firms to get a practising certificate, so this is an undeniable indicator of whether you are authorised or not. However, the implications are critical for anyone thinking of offering an alternative to law firms. Would you provide your expertise outside of a law firm if you can't get paid for it? By the way, it's a criminal offence too.

Let's say you want to practice law, but you don't want to be in a law firm. For example, maybe you aren't interested in the full service or boutique firm sort of business and are thinking of something radically different. Perhaps you would like to focus on a particular area of law and provide some consultancy, like Radiant Law (NB: Radiant Law is a law firm, more on this later). Maybe the business model is radically different. For example, some of your partners might be accountants or tech specialists, and you can't have them as directors or shareholders in a law firm without special approval.

This issue becomes thorny if you haven't considered it from the start. Imagine you think of an excellent idea for the public. You get funding from a VC, and the programmer who made this product is the other director of your company. If you didn't find out whether your company is providing legal services, you might well have doomed your project with the tint of illegality.

I know it when I see it.

Image by Kevin Phillips from Pixabay

Image by Kevin Phillips from Pixabay

So, what do you need to avoid if you do not want to provide legal services as an advocate and solicitor? Other than acts expressly prohibited under the Legal Profession Act, the case referred to the Turner test at [79] (emphasis added).

(a) Other than those specific acts listed in ss 30(1) and 30(2) of [the Legal Profession Act], an act is an act of an advocate and solicitor when it is customarily (whether by history or tradition) within his exclusive function to provide , e.g. giving advice on legal rights and obligations, drafting contracts and pleadings and pleading in a court of law.

(b) A person acts as an advocate and/or solicitor if, by reason of his being an advocate and solicitor, he is employed to act as such in any matter connected with his profession.

[2021] SGHC 154Tan Siong Thye J:The decision of Choo Cheng Tong Wilfred v Phua Swee Khiang

In the instant case, the lawyer might call himself a “business consultant”, but he gave legal advice (which the court noted is a quintessential service given by lawyers). Furthermore, the clients hired him because of his legal expertise. Therefore, the lawyer provided legal services as an unauthorised person and was not entitled to any fees for over a decade's worth of work.

I hate to say this, but the Turner test is an “I know it when I see it” test. If a user provides his own answers and an algorithm written by a lawyer turns it into a will, is the lawyer providing legal advice? If more law firms start to advise on adopting technology in contracting, would it become illegal for others to do the same?

Profound Implications

Image by S. Hermann & F. Richter from Pixabay

Image by S. Hermann & F. Richter from Pixabay

If the definition of providing legal services is too vague, that will cause a chilling effect on any product that borders on legal.

The reason why legal profession regulation is (perhaps) so restrictive is the protection of the public. The decision highlights two areas: lawyers with practising certificates can be regulated by the Law Society, and law firms pay insurance to cover professional negligence claims. There are several other rules relating to how a lawyer must undergo a practice management course before he can practice as an owner of a law firm or in his own name, and restrictions on management and ownership of law firms are also on this basis.

According to a recent article, this is perhaps a vivid illustration of why law firms or lawyers “will always be needed”. It's hard for me to imagine how jurisdictions will give up on protecting the public from fraudulent providers without some form of regulation. This kind of regulation would try to ensure some expertise behind products purporting to be legal.

On the other hand, it's hard to pin down what is unique about a lawyer's knowledge or expertise. With enough time on the job and the right training (not necessarily an LLB), Nonlawyers Can Be as Competent as Lawyers in Handling Contracts Work. In fact, lawyers might not possess all the skills required to study a legal process and figure out how to deliver it more efficiently or effectively. If lawyers can't do it properly, why can't someone else have a go at it?

For now, legal services backed by law firms seem to be the current equilibrium. Accounting firms like PwC have their own law firm. Radiant Law might not serve a client found on the street, but they are still a law firm. Perhaps we need a good rethink of what a law firm means today at some level. Furthermore, it would really help if the exceptions (if we have any) for non-traditional law firms were transparent.

Conclusion

Regulation is a serious roadblock if we want to see legal services being delivered in any alternative method. As Susskind and Eisenberg say, incorporating lawyers and law firms might be critical for alternative service providers to go around such issues. However, not everyone can incorporate a law firm or is willing to do this. Hopefully, the authorities can consider more transparent and sensible rules to limit the drawbacks of being unauthorised.

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow [this blog on the Fediverse]()

- Contact me:

The PracticeHLS Center on the Legal Profession

The PracticeHLS Center on the Legal Profession

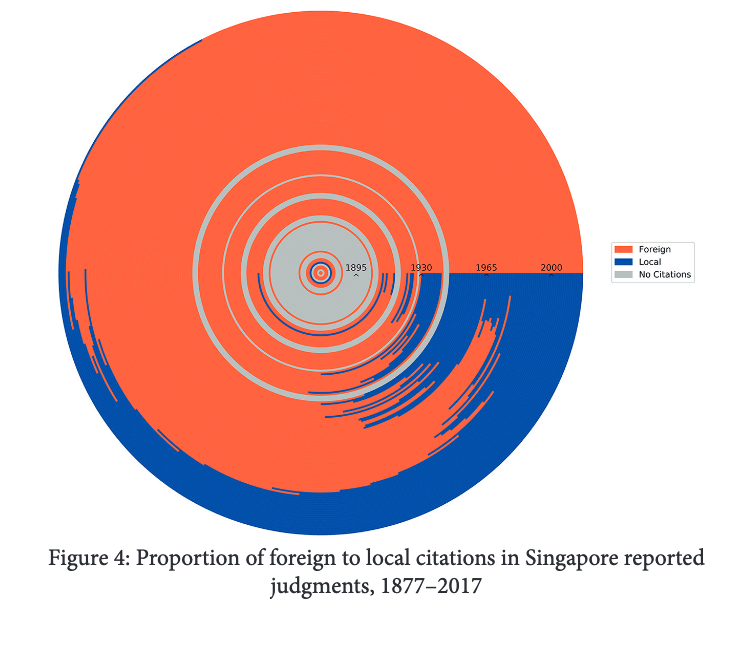

Phang Goh and Soh “THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE LAW: A BICENTENNIAL RETROSPECTIVE” at paragraph 62/page 32. (From

Phang Goh and Soh “THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE LAW: A BICENTENNIAL RETROSPECTIVE” at paragraph 62/page 32. (From

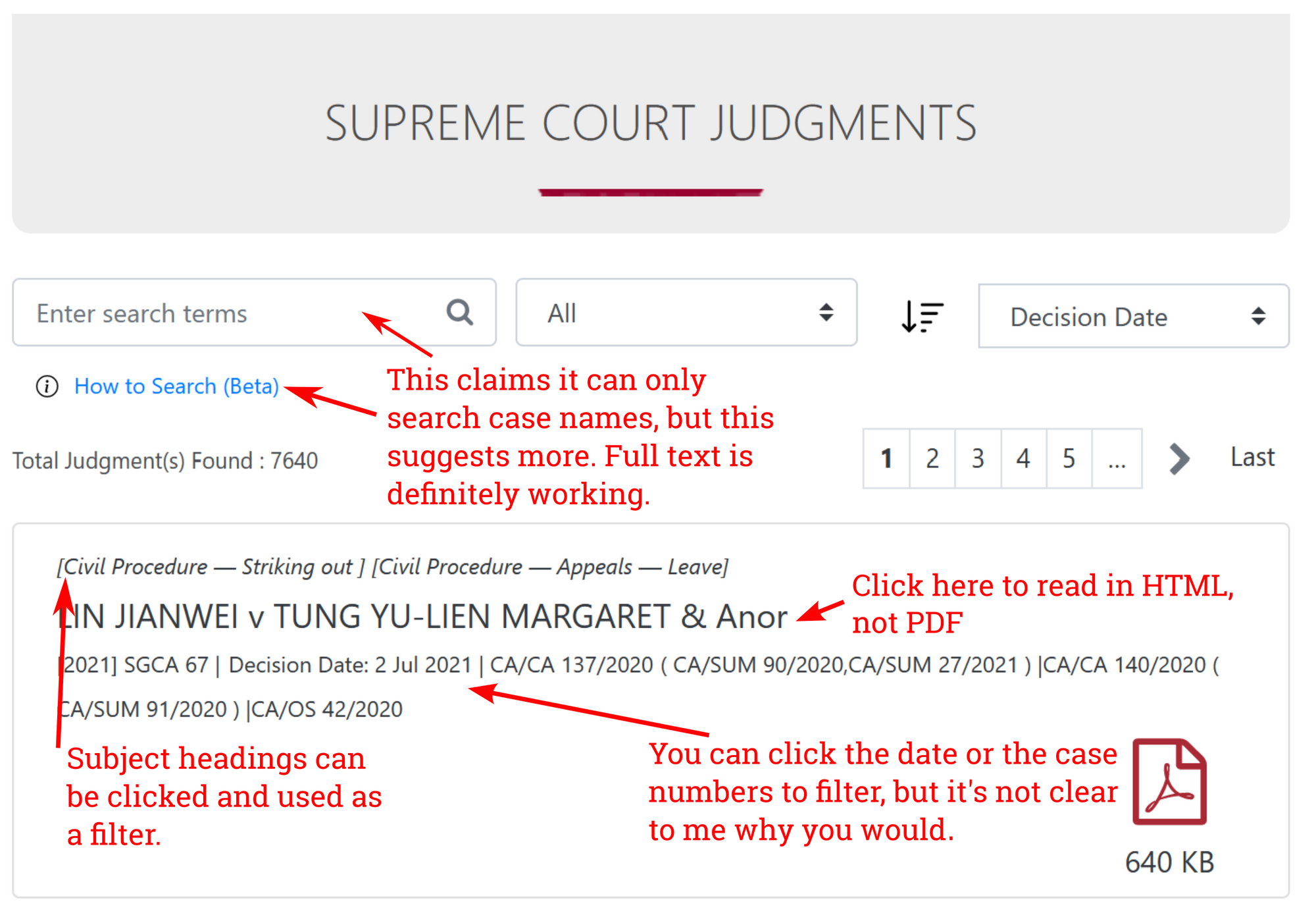

Legal Tech Jobs filtered for jobs with location “Singapore”. By the way, that single job does not require a computer science degree.

Legal Tech Jobs filtered for jobs with location “Singapore”. By the way, that single job does not require a computer science degree. Screenshot from

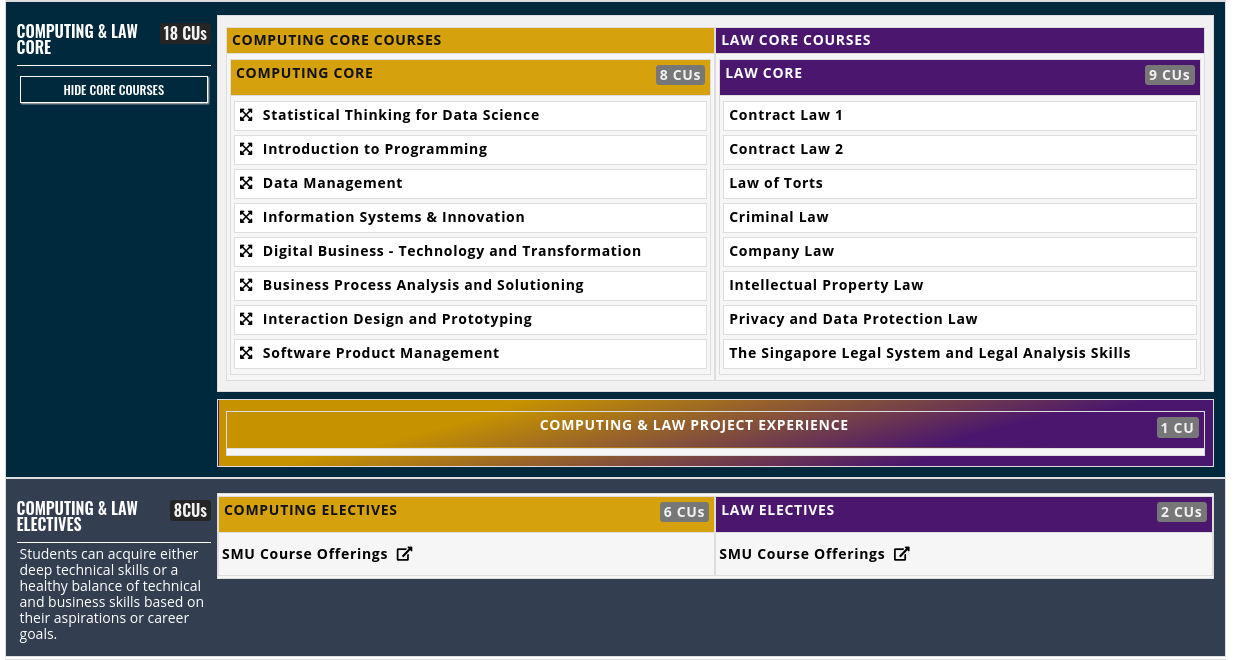

Screenshot from