It must be hard to be an NUS student these days. One of the top universities in Singapore (and Asia) keeps appearing in the news for naughty transgressions, and getting allegedly easy treatment from the courts. Arguing whether NUS students get preferential treatment touches on the fairness of the courts as well as whether those in the higher echelon of society get to enjoy privilege. Can exhortations on how the Court works overcome people’s innate fears and prejudices of those in power? I doubt it. More data is needed.

A strong desire to show that justice is done

An NUS student was initially sentenced to probation for molesting a woman in a train station. Probation is a process where once you complete its requirements without incident, ends in a clean record. Amidst a public outcry and the intervention of the law minister, the prosecution appealed. The High Court, presided by the Chief Justice, increased his sentence to two weeks of jail.

The judgements in this case are among the most fascinating.

The State Court isn’t wrong

The lower court (State Court) judgement is no longer available because LawNet only provides the latest three months for the public, so you would have to contend with my memory and a Mothership report.

The State Court judge wrote this during the public furore for the case. It contained a gem which rarely appears in judgements from the State Court: “ The order of probation should not be seen as a soft option. ” Sure, the State Court needs to justify its decision for scrutiny on appeal. However, claiming that probation is not a soft option appears to be a direct appeal to the public.

(By the way, when a State Court decision is appealed, the Court must write a judgement. Public attention and “pressure” as alleged by Mothership does not figure in this practice.)

The State Court’s reasoning appeared reasonable and in line with the sentencing practices of the Court. An appeal court can’t possibly substitute its decision for the State Court without explaining why the State Court is wrong. Will the appeal fail? Will the public see that justice is not “served”?

The Chief Justice cries foul

Key to justifying its decision to allow the appeal, the Chief Justice called for a psychiatric report of the accused. The report provided crucial pieces of information which the State Court did not have. The accused remained “in denial” of the offence. He was still doing pornography. He was able to “compartmentalise” his behaviour. As such, he failed to show an extremely strong propensity for reform. All this explained the State Court’s failure to reach the same decision as he did.

The Chief Justice’s conclusion: the system works.

The Chief Justice also remarked that he had on the same day, allowed another accused, who was “not a graduate”, to community-based sentencing. That case “did not attract any media or public interest”. The failure to report positive outcomes, the Chief Justice argued, creates the misconception that judges are not doing justice. These remarks were extraordinary because they usually do not appear in a court judgement.

Ironically, the media did not report the Chief Justice’s remarks. It is not surprising that the media does not report such positive outcomes and they do not figure prominently in the public’s mind. People react strongly to the oppression of the weak or when the powerful receive better treatment. That’s when they reach the conclusion that criminal justice is not working.

Another NUS student in hot soup

It has been only a few months since the Terence Siow case that another NUS student raised eyebrows again for getting probation. The new case shared many similar contours with Terence Siow’s case. They involved NUS students. The accused also perpetrated violence against females — Yin tried to strangle his girlfriend.

Would the criminal justice system now get an outcome which “aligns” with popular opinion again? If you were betting for such an outcome, the Terence Siow case actually shows that these things are by no means assured. For example, the Chief Justice can’t possibly know that Terence Siow was still watching porn when his case went up for appeal.

This may explain why, unlike Terence Siow, this case is not being appealed. The High Court recently dismissed an appeal from the prosecutor regarding an SMU student filming showers. The High Court in the latter case, stated that community-based sentencing is not a soft option.

Unable to satisfy the public through outcomes in the courts, the Ministry of Law announced a review of the penalty framework. It isn’t immediately clear (at least to me) what such a review would entail when the courts are adamant that the system is working. This is a developing issue, so more will come.

We can’t tell whether the system is working without data

Figuring out what to fix will be very difficult. We are not sure what we are trying to fix in the first place. Fundamentally, we do not know in the first place if university students receive “lighter” sentences because they are university students. It would be ironic if such a review attempts to raise the bar for probation and community sentences so high that even non-graduates cannot reach it.

There is scant public information on what goes on in the criminal justice system. We don’t know how often a graduate or a non-graduate gets away with “lighter” sentences. This provides fertile ground for suspicions, reinforcing personal experiences and even conspiracy theories. Solving this would entail analysing closely the decisions judges make with respect to each accused and the crime.

Such information might be available from appeal decisions, but they only represent a small subset of cases. In fact, such cases will probably over-represent graduates because they are more likely to appeal.

Having a data-driven approach solves two problems. The court will not be required to convince the public of esoteric legal concepts. The media will never report such complexity anyway either. We also do not have to decide whether the Chief Justice’s personal experience or the layman’s experience of the justice system is more compelling. The data can serve as a source of truth for our arguments to improve the system.

Barriers to a data-driven approach

Judges may not be comfortable having their decisions analysed in such detail. They may not like the data to show that someone is softer than the others on certain kinds of accused persons. However, if judges can remain steadfast in the face of public opinion, I am sure that a bunch of numbers are not going to overcome their desire to do right in the cases before them. Instead, such statistics may serve as another guardrail to remind judges when they are facing an outlier. This is nothing new — sentencing guidelines and appeals to higher courts already perform such checks.

I expect that the data is not going to be completely positive. The real fight in criminal matters, like most litigation, happens way before the Court hears the case. Getting referrals to a psychiatrist, writing contrite letters at the first opportunity, and testimonials from influential people can make the difference. It happens that graduates are more likely to get legal advice, know where to find a psychiatrist and have important people around them as well. It sounds unfair that well-resourced accused persons get lighter sentences, but to a judge, this is the evidence before him. If the Ministry’s review ends up increasing legal aid to many accused persons, that would be pretty great.

Of course, detailed data is not required to conclude that NUS students get off easier. However, if the ministry’s review ends up as a full-throated exhortation that the system works and it should work well for everyone, I am afraid we have learnt nothing much from this except whose opinion is stronger.

Conclusion

It’s great that young Singaporeans now care more about the criminal justice system and its outcomes. For many, this would be their first experience understanding the intricacies of this complex system. This is not the time to justify lofty concepts or point to personal experiences. It’s also great that the ability to analyse a judge’s decision-making in detail is largely available to us. Hopefully, this will spur better change to society’s benefit.

#Singapore #Law

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow [this blog on the Fediverse]()

- Contact me:

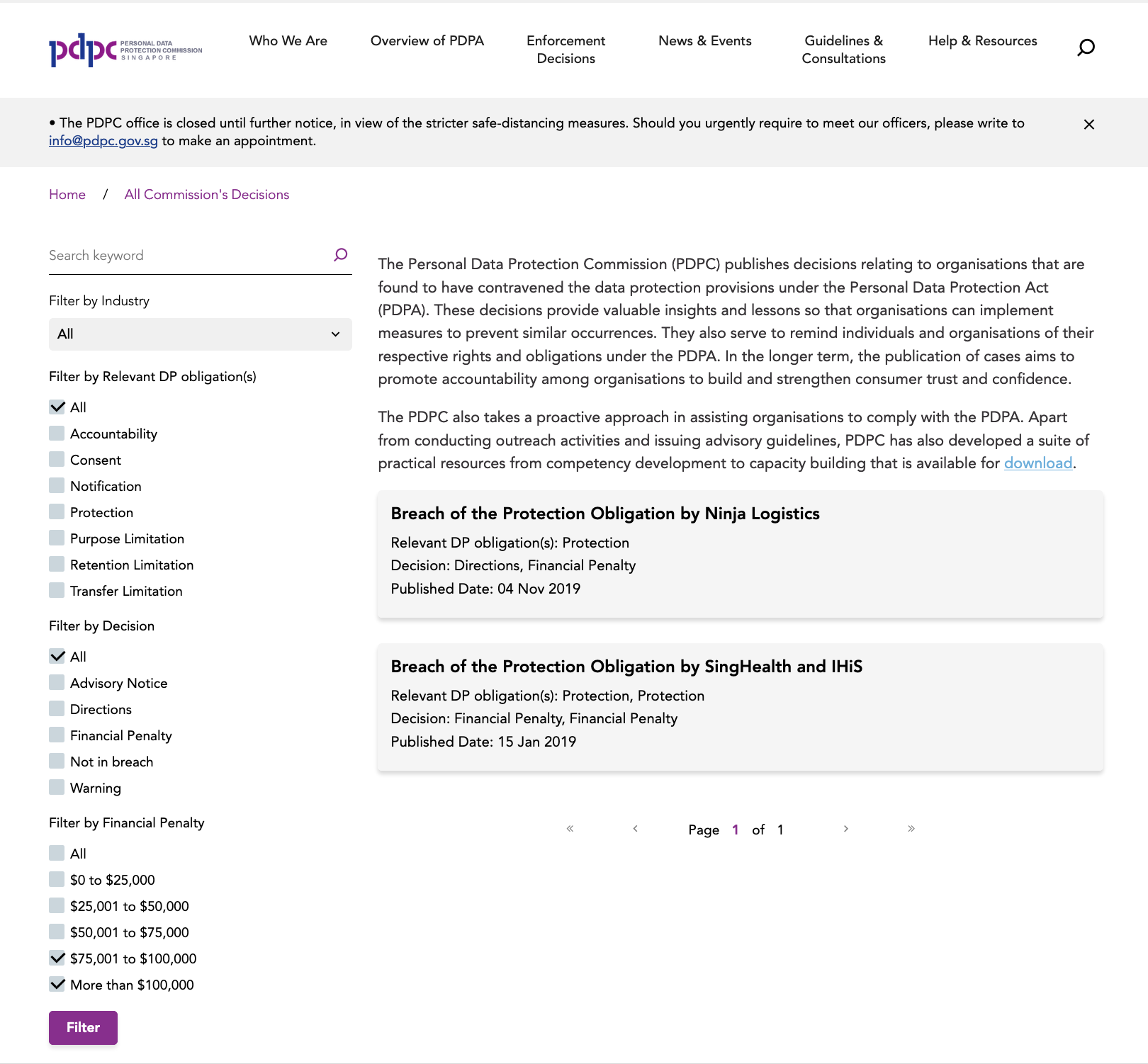

Screen capture of filters of PDPC decisions with financial penalties of more than $75000. (As of October 2020)

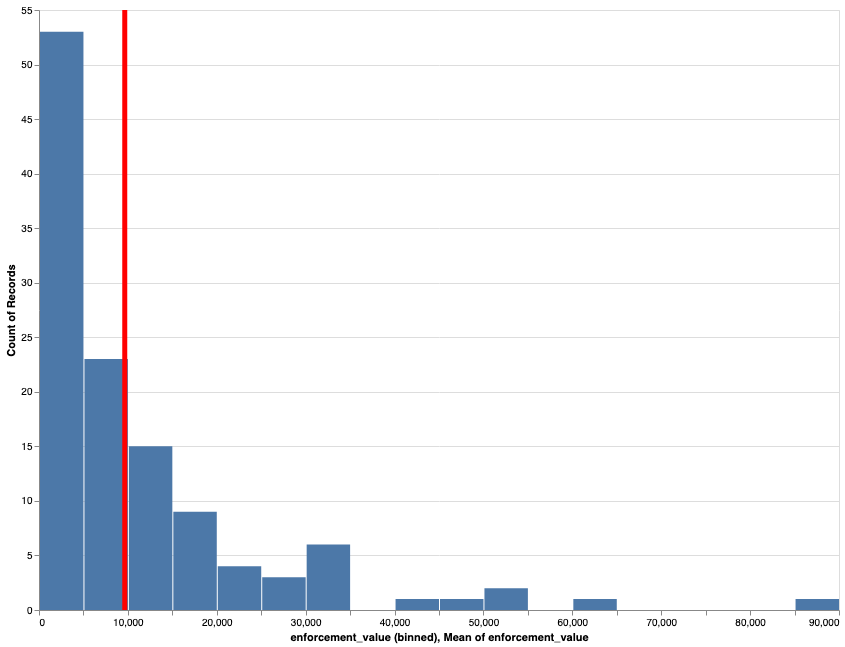

Screen capture of filters of PDPC decisions with financial penalties of more than $75000. (As of October 2020) Histogram of the number of cases binned on enforcement value.

Histogram of the number of cases binned on enforcement value.

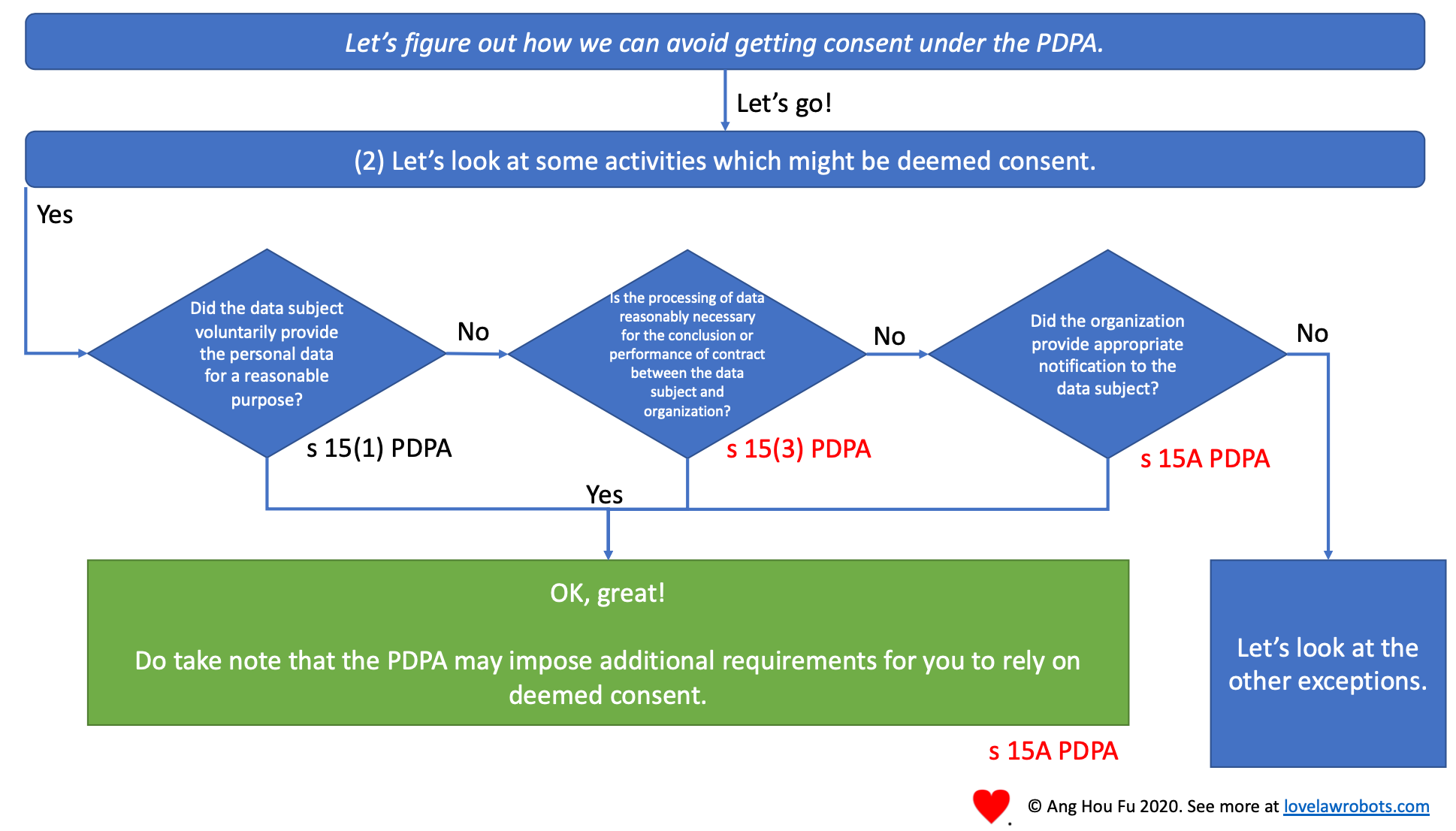

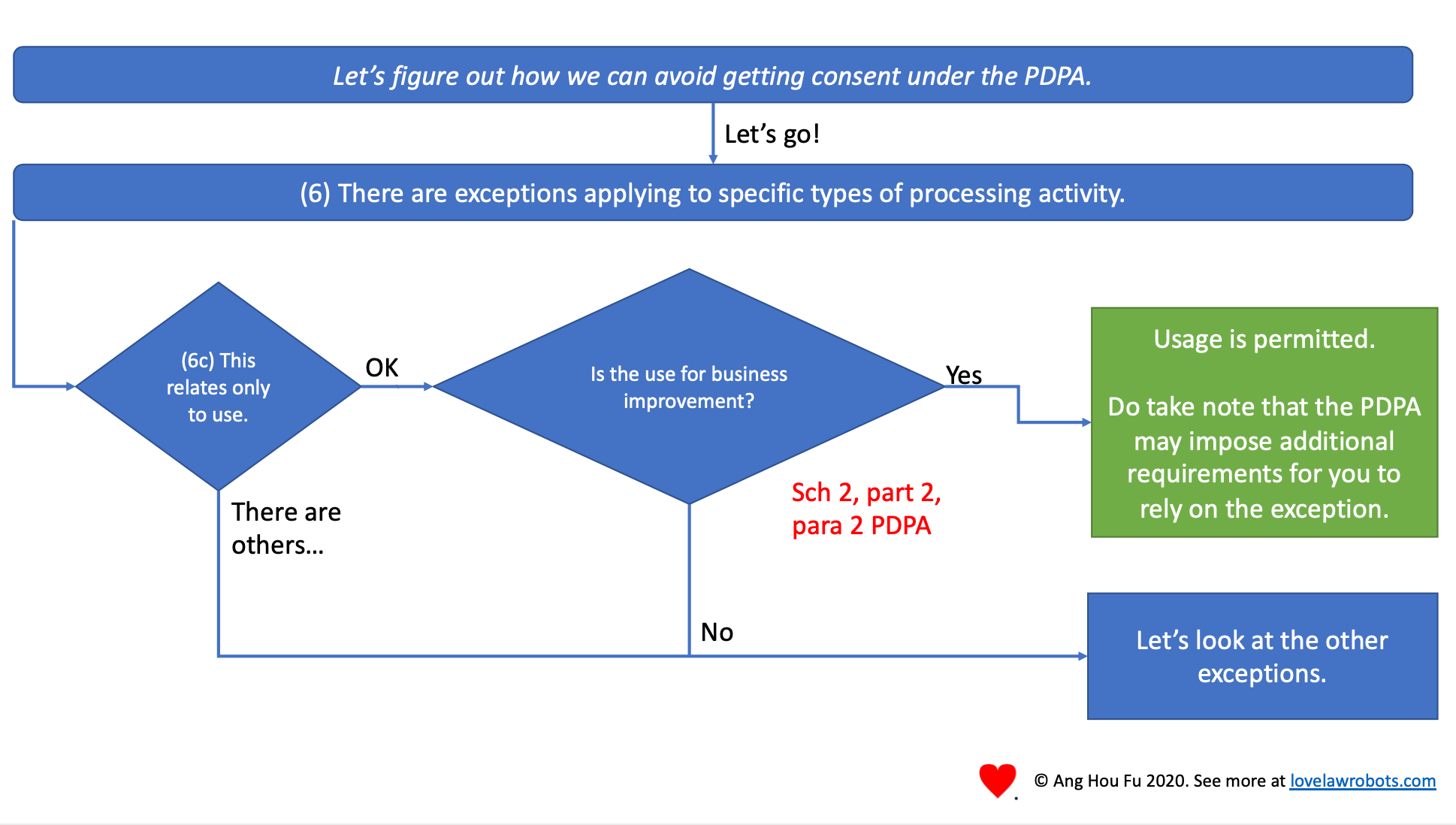

Deemed consent has expanded.

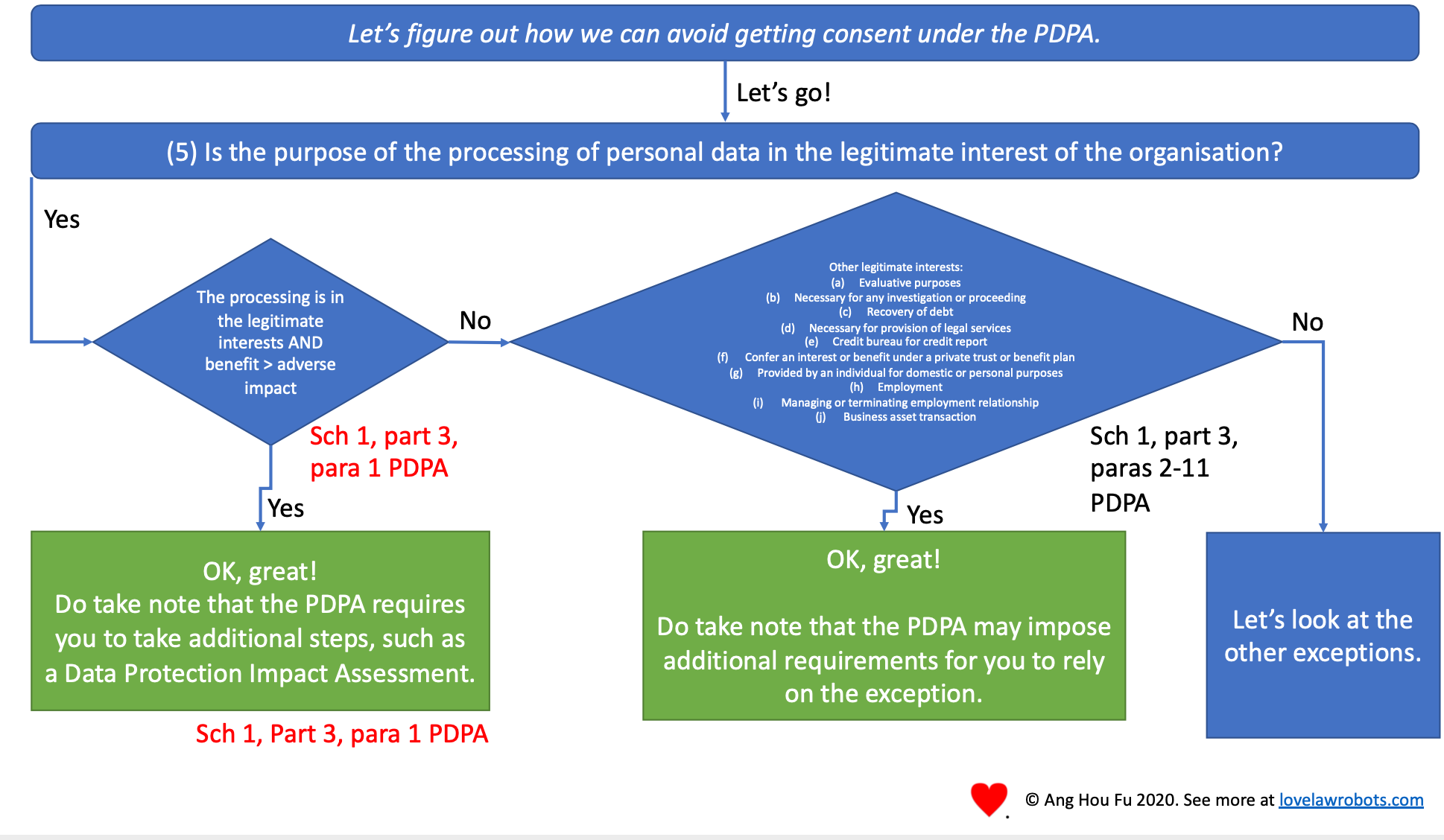

Deemed consent has expanded. A new legitimate interests exception.

A new legitimate interests exception.

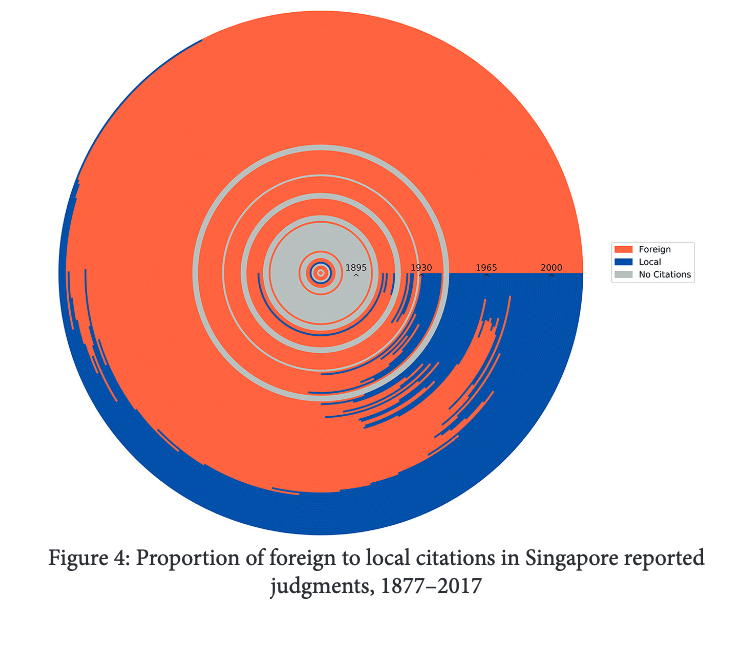

Phang Goh and Soh “THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE LAW: A BICENTENNIAL RETROSPECTIVE” at paragraph 62/page 32.

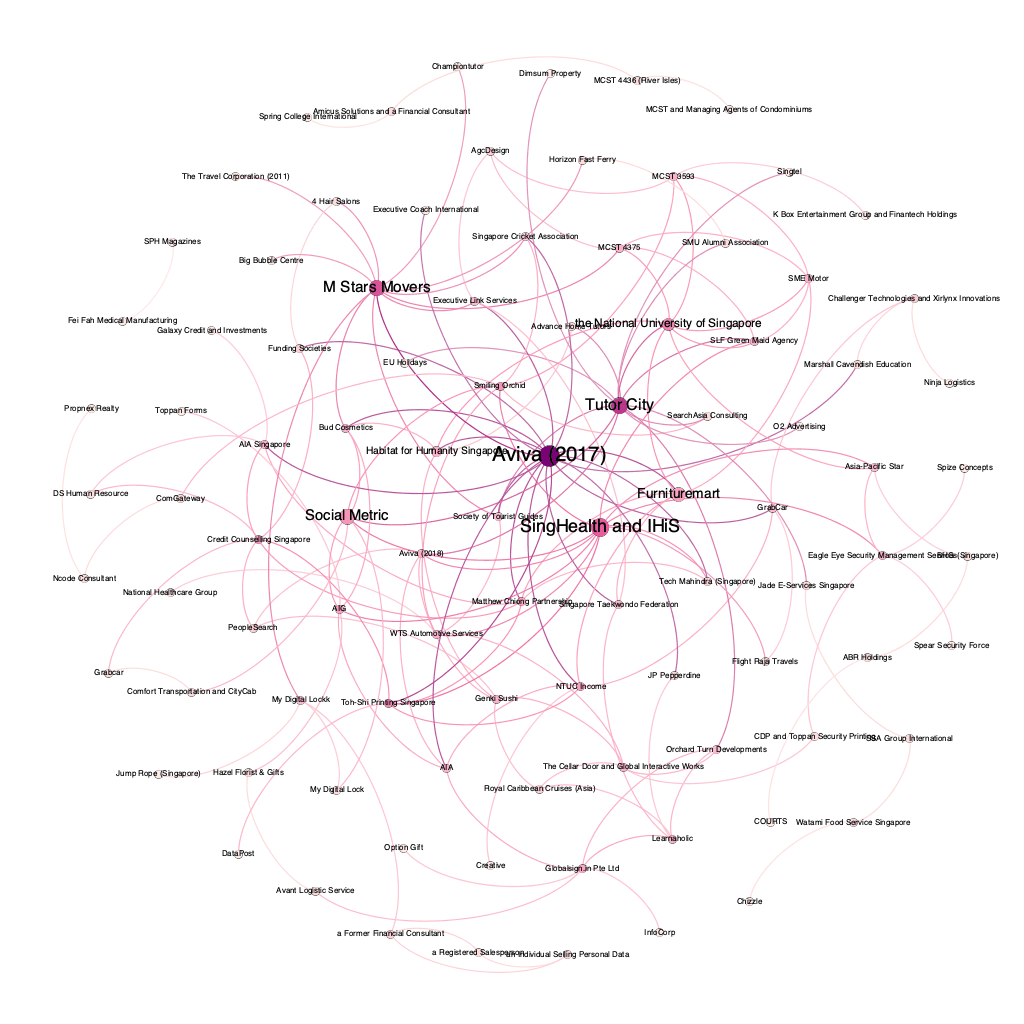

Phang Goh and Soh “THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE LAW: A BICENTENNIAL RETROSPECTIVE” at paragraph 62/page 32. It’s pink. What more can I say?

It’s pink. What more can I say?