ok first of all: obviously there are many robust emulators available that run games released for the Nintendo DS. drastic is the one I know of for Android; there’s desmume on PC; there are surely others.

speaking of Android: I recently got the Android-powered Anbernic RG405V, a 4:3-screen retro handheld with big DMG vibes:

(the wood grain looks as silly in person as it does in a photo. it’s a clever way to ensure that scuffs and scratches are never too visible, but it worked better when it was as a vinyl cover over my Guitar Hero III guitar controller many years ago.)

for the most part, the 405V is a fabulous emulation tool. its 4:3, 480p screen is pixel-perfect for home consoles predating widescreen television (GameCube or thereabouts), and it’s just performant enough to emulate all of those systems (though you’re pushing it if you try PS2 or GameCube). the hand-feel and controller layout blend retro and modern nicely, all things considered.

however: when playing around with this thing on a flight earlier this year, I decided to start playing 999: 9 Hours, 9 Persons, 9 Doors, a visual novel originally released on the Nintendo DS and later rereleased on PC and home consoles (we’ll get to that).

relevant tech specs: the Nintendo DS has dual screens each sporting a resolution of 256 x 192. that’s two 4:3 screens, one perched atop the other. the lower screen is a resistive touchscreen, designed in the pre-smartphone days. (you can mash your finger on it if you need to, but it’s meant for precise interaction via the included stylus.)

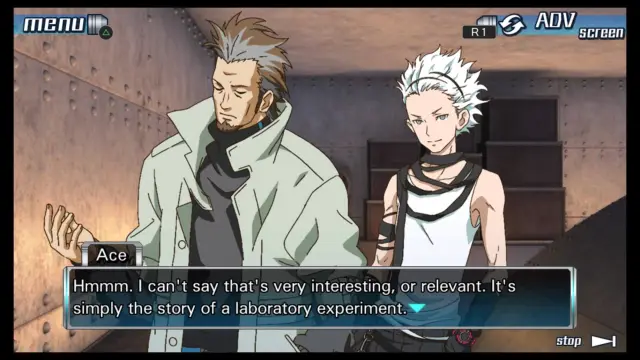

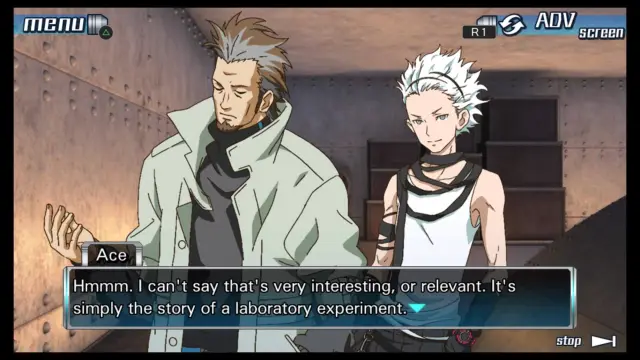

my primary issue when playing 999 on my 405V was that getting screen text readable on one of those screens too severely compromised the other. 999 takes advantage of its dual screens in non-gameplay segments by placing non-player character dialogue and portraits along the top screen, while third-person narration (including the protagonist’s dialogue and inner thoughts, as well as external action) plays out in tandem below:

this means there’s (pretty small to begin with!) text that needs to be read across both screens simultaneously. my options were a) map a button to drastic’s “switch screen” button and swap often to read each screen in full, or b) use a weird overlay with the “secondary” screen shrunken down to fit within the aspect ratio:

this works a bit better on the 405V than it looks here, because its higher resolution allows it to display the smaller screen more clearly, but it’s still an eyesore. the overlay also creates problems when you need to see or interact with something on your current “primary” screen while it’s covered by the “secondary” screen.

interaction creates whole other problems. the screen’s still not ideal, for one, as the game clearly often expects you to be able to see both screens during gameplay:

…but even if you manage to find a comfortable compromise there, you run into the other major issue: the DS’s touchscreen.

this hardware feature creates two problems for android gaming handhelds like the 405V. one is that, though these devices usually have a touchscreen, they’re not designed with touch as a primary interaction. imagine having to take a hand off your classic Game Boy to prod at the screen. it’s not great.

the other issue is that, again, the DS screen was resistive and more-or-less required the use of a stylus. 999 knows this and demands corresponding precision that’s hard to replicate with a finger. the DS stylus also covered much less of the screen than a finger; your visibility was not supposed to be compromised while you played.

the result is clunky even after you sort out these issues. ultimately I sought other means to play the game. soon I realized that every option outside of native hardware was going to run into the issues I outlined above to some degree or another, no matter what.

the shame is that I have, in theory, the perfect type of device to emulate DS and 3DS alike: a foldable phone. ever since the advent of these too-expensive, too-delicate pieces of tech, people have made drastic skins to transform their foldables into a surprisingly convincing simulacrum of the real deal:

I can confirm this is as cool to behold in person and in your hands as it is in the photograph! unfortunately I must also confirm that pressing touchable zones on a phone screen remains an awful replacement for real buttons when playing games designed for the latter. note too the conspicuous absence of shoulder buttons: you’re forced to drop those in unnaturally around the facade (I put mine basically just below the hinge).

what you get is a closer visual cousin to the original experience, but still something definitively worse to play. visual novels like 999 work OK in this set up, but game-ier games like, say, mario kart DS are a nonstarter.

there are plenty of devices that can more than ably output the software experience of a DS — properly rendered graphics, responsive input/output, and so on — but software emulation definitionally cannot replicate hardware and input methods, and the DS is one of the most unique gaming hardware designs in history.

nintendo has a long history of such designs — hell, you can go back as far as the Virtual Boy. dolphin, a longstanding and well-polished GameCube and Wii emulator, can run near any Wii game flawlessly (even upscaled to 1080p or 4k), but if you haven’t connected a Wiimote to your PC emulator box, you’ll struggle with any game that took any advantage of the unique control possibilities.

(this is a real problem I’ve dealt with a few times — not with games like Resident Evil 4, where the then-revolutionary pointing precision can be mapped well to a mouse or even a gyro-assisted right analog, but with Super Mario Galaxy 2. that’s a game in the rarefied air of Games I’ve 100% Completed, but I haven’t gone back to it since I played it on a Wii over a decade ago. most of its controls work fine, but its star collection-and-use mechanics are intolerable without real IR-pointer controls. you just end up with this stupid blue star stuck on the center of your screen every moment you aren’t using the right stick or some other imprecise and frustrating controller input to move it. yoshi’s a pain in the ass, too. one of the most purely fun games I remember playing isn’t fun anymore, when played this way.)

again, dolphin is maybe the most polished and impressive emulator ever built. it absolutely can emulate Wii games, most of them perfectly even on an older PC, but it cannot replicate the experience of sticking an IR sensor onto the top of a dorm room’s 20-inch CRT unless you happen to also own those things.

for now there are relatively cheap hardware solutions for that, and Wiimotes are still in relative abundance. you can see this landscape shifting as time passes, though. I switched to playing 999 on my old DS Lite but soon found it too small and cramped for comfort, and it was a huge pain sifting through listings to find a DSi XL in decent enough shape to be worth picking up that didn’t cost extra hundreds of dollars—simply because hardware like this is now a collector’s item, transitioning from obsolescence into scarcity.

the hardware-software mind meld is a vital piece of the home console and handheld gaming experience, and it’s a lot harder to preserve over time than the software, which already struggles with proper preservation due to the ongoing efforts of companies like nintendo, for whom IP control supersedes the historical record.

this is the flip side of what I was talking about with romhacks. community preservation efforts can often create something more modern and playable than most studios’ own remasters and remakes, but they’re much less able to capture the authentic and holistic experience of playing those games for the first time in their original context.

context is crucial for understanding art! it also decays over time for all media. fascinating debates abound regarding appreciation of works with decayed contexts. like, what should it mean to how we perceive ancient Roman statues that in their time they probably looked more like carnival clowns? how do you balance an analysis of beowulf’s storytelling or thematic power against its status a work that comes to us incomplete and heavily reworked by the Christian monks who recorded it?

and since interaction is core to the videogame medium, hardware “context” is essential. even as a simple work of human effort, it’d be much harder to appreciate the statue of david if you had to view it through a foggy mirror, or the divine comedy if no translated existed in your language.

if you tried to play devil may cry on your phone using touch controls, and you thought that was the intended way to play devil may cry, you’re going to think that devil may cry is a very bad game designed by idiots. actually, trying to play dmc that way feels closer to viewing a statue while altogether blind.

perhaps this doesn’t need to be framed as dire, though. maybe it is a phenomenon closer to marble Roman statues, where for one thing new beauty and worthwhile strangeness can arise in half-preserved experiences overlaid upon new, modern forms of interaction or perception. that’s a nice idea. for example, I like playing emulated SNES games on a modern controller, where quality-of-life features like fast forward or save states are easily mappable to otherwise-unused buttons. old software and new hardware create something new that can inform and articulates something about each. all well and good.

but then again, mass-released games aren’t just art, are they? they’re commodities, compromised at every turn by corporate considerations. the easiest way to play 999 now is through a steam remake/rerelease that by necessity collapses the dual screens, and essentially loses half of the game’s intended visual information, creating an intended experience similar to my severely compromised 405V one:

from what I’ve heard, the rewriting and reworking done as part of making this feasible does real damage to the game’s writing and storytelling. what I’ve heard is also enough to leave me uninterested in buying the remake; doing so knowing of the original experience would feel too much like trying to play devil may cry blindfolded.

(POSTSCRIPT, WITH VAGUE 999 SPOILERS: having now finished 999, I simply cannot believe I wrote this whole thing before completing the game. if I work this script into a youtube video at some point, it’ll probably have a spoiler-heavy section on just how much 999’s whole narrative structure relies on the DS hardware.)