Part 1: Caught in the Patty Vault

Who else feels attacked when they see this face?

I keep hearing that you only understand Squidward when you grow up: as a kid you identified with SpongeBob because you used to be like him (a happy innocent creative playful silly childlike haver of fun), and then you got old and crusty and turned into Squidward (a boring nasty cynical anguished self-defeating narcissistic grump). The general idea gets spelled out pretty well in this video essay, and you can see people repeating the thesis in just about every YouTube comment on every Squidward video.

But I saw the show as a kid, and I remember identifying with Squidward. When he was frustrated, I was frustrated; when he was embarrassed, I was embarrassed. I remember a hostile universe that was set up fully against Squidward. The poor guy was just stuck in despair at the bottom of the sea, playing his clarinet, badly, forever. That's how I saw it. How could you possibly identify with SpongeBob?

Let me be precise. I don't mean identifying with SpongeBob in general—of course you could relate to SpongeBob in those episodes when he deals with procrastination, or flunks his driver's exam, or forgets how to tie his shoes. I mean that I find it hard to see how you could relate to SpongeBob in his role in Squidward's life. In the classic episodes about the dynamic between SpongeBob and Squidward, SpongeBob comes off as an intrusive nuisance, a weird alien, a smiling monster—-not as somebody you could be.

The Squidward episodes I remembered most clearly were “Idiot Box” (the one where SpongeBob and Patrick play with their imagination and make impossibly real noises whenever Squidward isn't looking), “Just One Bite” (the one where Squidward tries a Krabby Patty for the first time), and “Artist Unknown” (the one where Squidward tries to teach SpongeBob the rules of art, but SpongeBob is naturally perfect at it). Looking back on these episodes, I remembered a very anti-rational, anti-snobbish, aggressively populist worldview—one that says, “Everyone who claims to be sophisticated is full of shit and denying their sense of fun. Look at SpongeBob. You would be talented like him if you just let go of your ego and stopped trying to live by all these pompous, made-up, adult rules. You should be a SpongeBob and not a Squidward.“

Well, that was the impression I had, looking back on the show. but I hadn't seen SpongeBob in a long time. So in early 2020 quarantine, I rewatched a whole lot of Squidward episodes from the first three seasons—all the ones I remembered, some I had forgotten, and some I had never heard of. I wanted to see if they really had the message I thought they had, or if I had just been projecting my insecurities on the show retroactively. Well—it turns out I had it completely backwards!

Each of these Squidward episodes is a caricature of Squidward's predicament. It's not that the show's message is “Fuck you, Squidward, for being a Squidward”—it's that when you're in Squidward's place, the universe seems to be saying that. The show isn't saying that talent and creativity belong to childlike innocent happy fun people—it's saying that from Squidward's position, happy talented people look like these smiling monsters. It's not saying people are permanently in one category or the other, SpongeBob or Squidward—it's describing the delusion that makes you essentialize people into SpongeBobs and Squidwards. I'm not saying the cartoon has to be a real description of anything; I'm saying it articulates the fantasies and delusions involved in a deeply unhealthy relationship with talent and ego.

Watching these episodes, I noticed a pretty common pattern:

- Squidward tries to enjoy himself, but he gets interrupted by the intrusion of SpongeBob (and maybe Patrick).

- SpongeBob shows off some kind of incomprehensible magic (an object or talent), which Squidward outwardly rejects.

- SpongeBob takes Squidward’s rejection seriously, while Squidward becomes obsessed with the magic.

- Squidward gives in to secret desire and tries to get the magic himself, often in private. SpongeBob catches Squidward in the act.

- Squidward goes overboard somehow and gets punished by fate.

I see this as the basic pattern of these episodes: Bubblestand, The Paper, Artist Unknown, Just One Bite, Idiot Box, and Club SpongeBob.

Each one of them has an unattainable object—some kind of locus of the fun that Squidward doesn't want to have, then wants to have, then can't have, then gets punished for seeking. Sometimes it's a physical object (the paper, the Krabby Patty), and other times it just seems to be an incomprehensible talent (drawing a perfect circle, blowing elephant bubbles). “Club SpongeBob” actually has two copies of this pattern, with two such objects: first the unattainable thing is club membership, and then it's the magic conch, a pull-string toy that gives vague commands to be obeyed.

Why does this story keep happening? What does it say about Squidward, who is so committed to his persona that he can only transgress its mandates in private? What does it say about the world, that keeps clocking him on it and humiliating him for it?

I wrote a more detailed analysis of each episode and how it relates to Squidward:

- Commentary: Bubblestand

- Commentary: The Paper

- Commentary: Artist Unknown

- Commentary: Just One Bite

- Commentary: Idiot Box

- Commentary: Club SpongeBob

Of course, there must be more than just these. I'm sure you could find examples from season four and beyond, but by that time the creators had built the characters and situations, wound them up, and set them down; and away they went cluttering like hey-go-mad, treading the same steps over and over again, until they made a road of it, as plain and smooth as a garden-walk. It would be surprising if SpongeBob and Squidward didn't go on doing the same bit. So I'm not going to write about them unless they reveal a new dimension to the Squidward/SpongeBob dynamic.

On the other hand, there are some wonderful episodes that don't fit this formula at all. I certainly hope to analyze some of the episodes where Squidward gets exactly what he wants, and hates it. I also want to look at episodes like “Pizza Delivery” and “Fools in April,” which have their own memorable Squidward arcs. But these will have to wait for a later post.

When SpongeBob's butterfly bubble pops on Squidward's forehead, he says, “That's not art. That's just annoying! Blowing bubbles—that's just the lamest idea I've ever heard!”

When SpongeBob's butterfly bubble pops on Squidward's forehead, he says, “That's not art. That's just annoying! Blowing bubbles—that's just the lamest idea I've ever heard!” Squidward, alone, chuckles to himself, “Hmm hmm. Bubbles. Hm hm. Art.” And he keeps muttering, but starts glancing around him, and notices nobody's around him to see. He sniffs the wand and picks it up.

Squidward, alone, chuckles to himself, “Hmm hmm. Bubbles. Hm hm. Art.” And he keeps muttering, but starts glancing around him, and notices nobody's around him to see. He sniffs the wand and picks it up.

Squidward pays, and blows the most pitiful bubble you've ever seen, and it pops with a fart noise at his feet.

Squidward pays, and blows the most pitiful bubble you've ever seen, and it pops with a fart noise at his feet.

He screams his lungs out into the bubble wand.

He screams his lungs out into the bubble wand.

The bubble, a product of his rage, lifts into the sky. As Squidward's house is going up, he plays the clarinet, beautifully, and SpongeBob and Patrick cheer for him.

The bubble, a product of his rage, lifts into the sky. As Squidward's house is going up, he plays the clarinet, beautifully, and SpongeBob and Patrick cheer for him.

The bubble lifts Squidward's house up to the sky.

The bubble lifts Squidward's house up to the sky.

It pops, and his house comes crashing down.

It pops, and his house comes crashing down.

SpongeBob picks it up and asks Squidward if he wants it back.

SpongeBob picks it up and asks Squidward if he wants it back.

SpongeBob plays tricks with the paper, which go from impressions to impossible, magical feats. Squidward watches from behind some coral as SpongeBob plays tricks with the paper, admitting it does seem like fun.

SpongeBob plays tricks with the paper, which go from impressions to impossible, magical feats. Squidward watches from behind some coral as SpongeBob plays tricks with the paper, admitting it does seem like fun.

Then Squidward tries to have fun himself, but SpongeBob proves that he can do better with the paper than Squidward can do with anything else, even playing music better than Squidward can on his clarinet.

Then Squidward tries to have fun himself, but SpongeBob proves that he can do better with the paper than Squidward can do with anything else, even playing music better than Squidward can on his clarinet.

He even has flip book footage! Squidward offers to trade. He gives away all his stuff, including the shirt off his back!

He even has flip book footage! Squidward offers to trade. He gives away all his stuff, including the shirt off his back!

These are obviously not jokes, and he's obviously not enjoying the magazine. It's as if Squidward is performing adulthood: not simply being an adult and enjoying his own interests, but acting for an unseen audience, demonstrating outwardly the interest in whatever he thinks adults are supposed to be interested in. This is why I can't agree with the claim that Squidward is who we all become as grown-ups: rather, Squidward is a child's idea of a grown-up.

These are obviously not jokes, and he's obviously not enjoying the magazine. It's as if Squidward is performing adulthood: not simply being an adult and enjoying his own interests, but acting for an unseen audience, demonstrating outwardly the interest in whatever he thinks adults are supposed to be interested in. This is why I can't agree with the claim that Squidward is who we all become as grown-ups: rather, Squidward is a child's idea of a grown-up. “What am I saying?” he says, shocked at himself.

“What am I saying?” he says, shocked at himself.

...or psychologically, as when Squidward accidentally paints himself with the paper on his nose.

...or psychologically, as when Squidward accidentally paints himself with the paper on his nose.

Is it possible for Squidward to have spoken through the dummy without realizing what he was saying? Apparently. Anyway, SpongeBob tells a joke and a crowd of anonymous fish appear JUST to laugh and vanish. The last straw is when SpongeBob plays better clarinet with the paper than Squidward can: clarinet is the one last thing Squidward can do that makes him feel special, and SpongeBob takes away even that power.

Is it possible for Squidward to have spoken through the dummy without realizing what he was saying? Apparently. Anyway, SpongeBob tells a joke and a crowd of anonymous fish appear JUST to laugh and vanish. The last straw is when SpongeBob plays better clarinet with the paper than Squidward can: clarinet is the one last thing Squidward can do that makes him feel special, and SpongeBob takes away even that power.

“Ah, how I have dreamed of this day: Mr. Tentacles, professor of art. What a marvelous opportunity for the people of Bikini Bottom. Bring me your huddled masses of bored housewives, and I will shape them in MY image.” It's nine AM, and he opens the doors to let the students in, but—horror of horrors!—his only student is SpongeBob.

“Ah, how I have dreamed of this day: Mr. Tentacles, professor of art. What a marvelous opportunity for the people of Bikini Bottom. Bring me your huddled masses of bored housewives, and I will shape them in MY image.” It's nine AM, and he opens the doors to let the students in, but—horror of horrors!—his only student is SpongeBob.

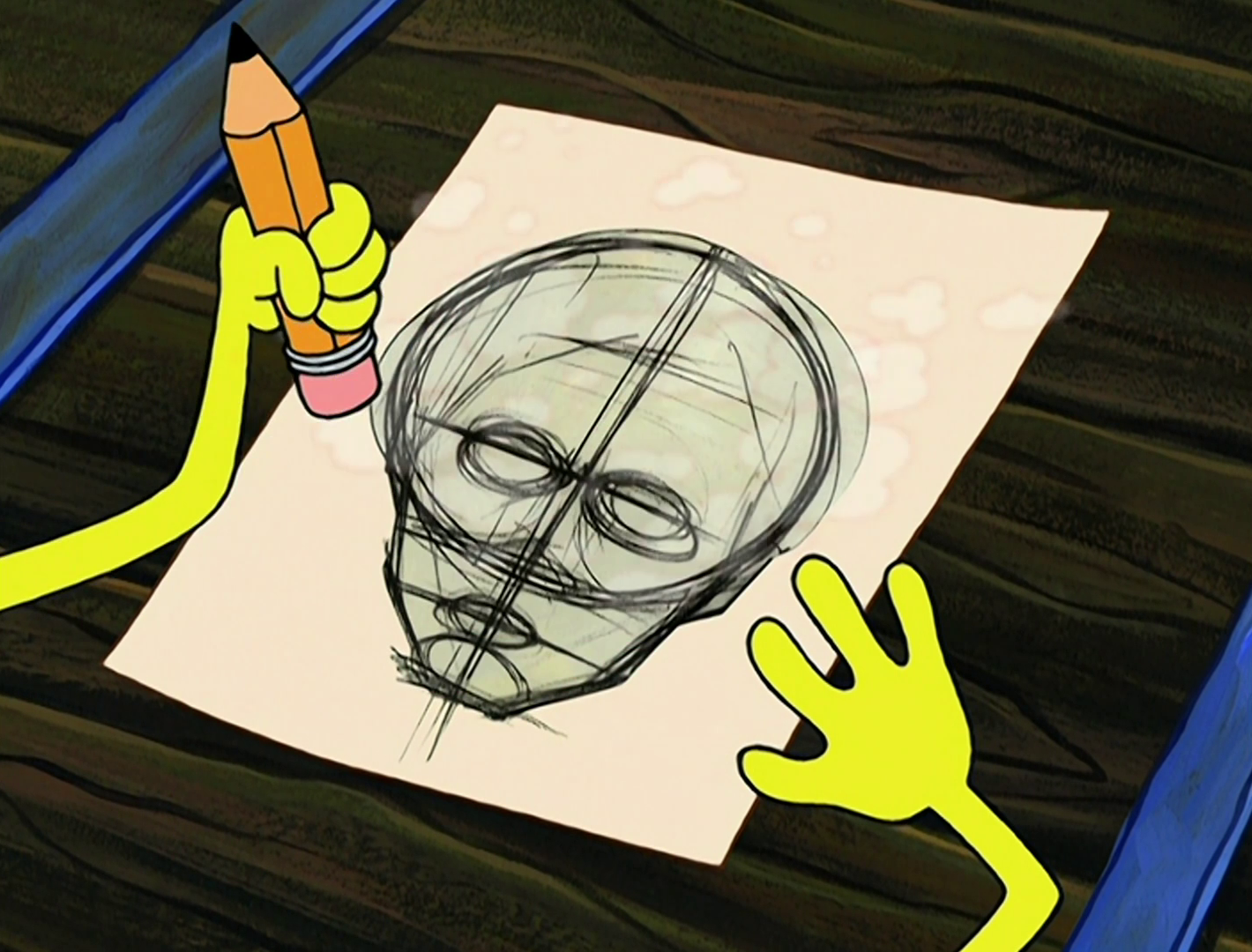

His method is ridiculous: draw a head construction in reverse.

His method is ridiculous: draw a head construction in reverse.

Squidward gets mad and balls up the paper: “Forget the circles.” SpongeBob also folds up paper—into a kinetic origami piece of SpongeBob and Squidward playing leapfrog.

Squidward gets mad and balls up the paper: “Forget the circles.” SpongeBob also folds up paper—into a kinetic origami piece of SpongeBob and Squidward playing leapfrog.

Squidward tears up the paper and SpongeBob makes a picture out of the scraps.

Squidward tears up the paper and SpongeBob makes a picture out of the scraps.

“It's beautiful!” Squidward says, his persona slipping a little. Grasping for something to criticize about the sculpture, he pulls out a book called The Rules of Art, and sticks a Squidward nose on David's head.

“It's beautiful!” Squidward says, his persona slipping a little. Grasping for something to criticize about the sculpture, he pulls out a book called The Rules of Art, and sticks a Squidward nose on David's head.

SpongeBob earnestly cries about how bad he is, although Squidward knows SpongeBob is a genius.

SpongeBob earnestly cries about how bad he is, although Squidward knows SpongeBob is a genius.

It's interesting here that SpongeBob saying what Squidward clearly wanted to hear doesn't make Squidward happy: he just looks conflicted and guilty.

It's interesting here that SpongeBob saying what Squidward clearly wanted to hear doesn't make Squidward happy: he just looks conflicted and guilty. The statue gets broken, and Squidward promises the collector something that will knock his socks off. He finds SpongeBob in the dump. Squidward coaxes him back, but SpongeBob has lost his gift—BECAUSE he's adopted the rules of art!

The statue gets broken, and Squidward promises the collector something that will knock his socks off. He finds SpongeBob in the dump. Squidward coaxes him back, but SpongeBob has lost his gift—BECAUSE he's adopted the rules of art! He leaves before he could discover that he accidentally made an even better David—but the janitor gets the credit.

He leaves before he could discover that he accidentally made an even better David—but the janitor gets the credit.

Squidward's artificial nose goes on and off the statue, and his real nose even drips off his face and plops onto the floor, when SpongeBob recreates The Rules of Art.

Squidward's artificial nose goes on and off the statue, and his real nose even drips off his face and plops onto the floor, when SpongeBob recreates The Rules of Art.

I'm not going anywhere with this, but it reminds me of Jiří Trnka's The Hand, where a large disembodied hand invades a potter's little house and compels him to make replicas of itself.

I'm not going anywhere with this, but it reminds me of Jiří Trnka's The Hand, where a large disembodied hand invades a potter's little house and compels him to make replicas of itself.

Squidward does want to shape the huddled masses in his image, and his oeuvre is pretty much entirely squids, so maybe there's fruit for comparison there.

Squidward does want to shape the huddled masses in his image, and his oeuvre is pretty much entirely squids, so maybe there's fruit for comparison there.

We have the following mini-episode:

We have the following mini-episode:

SpongeBob and Patrick just sit there, and a beautiful picnic falls out of the sky for SpongeBob and Patrick.

SpongeBob and Patrick just sit there, and a beautiful picnic falls out of the sky for SpongeBob and Patrick.

This annoys Squidward enough that he confronts them about it.

This annoys Squidward enough that he confronts them about it. Squidward dismisses the thought and takes their TV.

Squidward dismisses the thought and takes their TV.

When Squidward opens the box, SpongeBob and Patrick are just sitting there, playing pretend.

When Squidward opens the box, SpongeBob and Patrick are just sitting there, playing pretend.

When Squidward tries to enjoy TV, everything on there is about boxes.

When Squidward tries to enjoy TV, everything on there is about boxes.

He thinks they must be fooling him with a tape recorder, so he sneaks in at night.

He thinks they must be fooling him with a tape recorder, so he sneaks in at night.

Of course, this is a dump truck hauling him away.

Of course, this is a dump truck hauling him away.

Squidward not only has an imagination, it's powerful enough to control him, to mess up his life. But in contrast with SpongeBob, Squidward has no power over it. When it comes to imagination rainbows, he's impotent.

Squidward not only has an imagination, it's powerful enough to control him, to mess up his life. But in contrast with SpongeBob, Squidward has no power over it. When it comes to imagination rainbows, he's impotent.

Finally Squidward caves in and tries it. He makes a show of tasting it: he pretends to love it for a split second, then calls it disgusting and stomps it into the ground.

Finally Squidward caves in and tries it. He makes a show of tasting it: he pretends to love it for a split second, then calls it disgusting and stomps it into the ground.

He realizes he needs to get his hands on a Krabby Patty, but without SpongeBob seeing: “After that performance, he would never let me live it down.”

He realizes he needs to get his hands on a Krabby Patty, but without SpongeBob seeing: “After that performance, he would never let me live it down.”

Squidward pretends that somebody else has ordered a Krabby Patty. While SpongeBob is flipping Krabby Patties on the grill and the sight and smell is making Squidward's pupils dance in his eyeballs, SpongeBob apologizes—just when it hurts. SpongeBob comes out calls out for whoever ordered the patty—and eats it himself, with Squidward watching!

Squidward pretends that somebody else has ordered a Krabby Patty. While SpongeBob is flipping Krabby Patties on the grill and the sight and smell is making Squidward's pupils dance in his eyeballs, SpongeBob apologizes—just when it hurts. SpongeBob comes out calls out for whoever ordered the patty—and eats it himself, with Squidward watching!

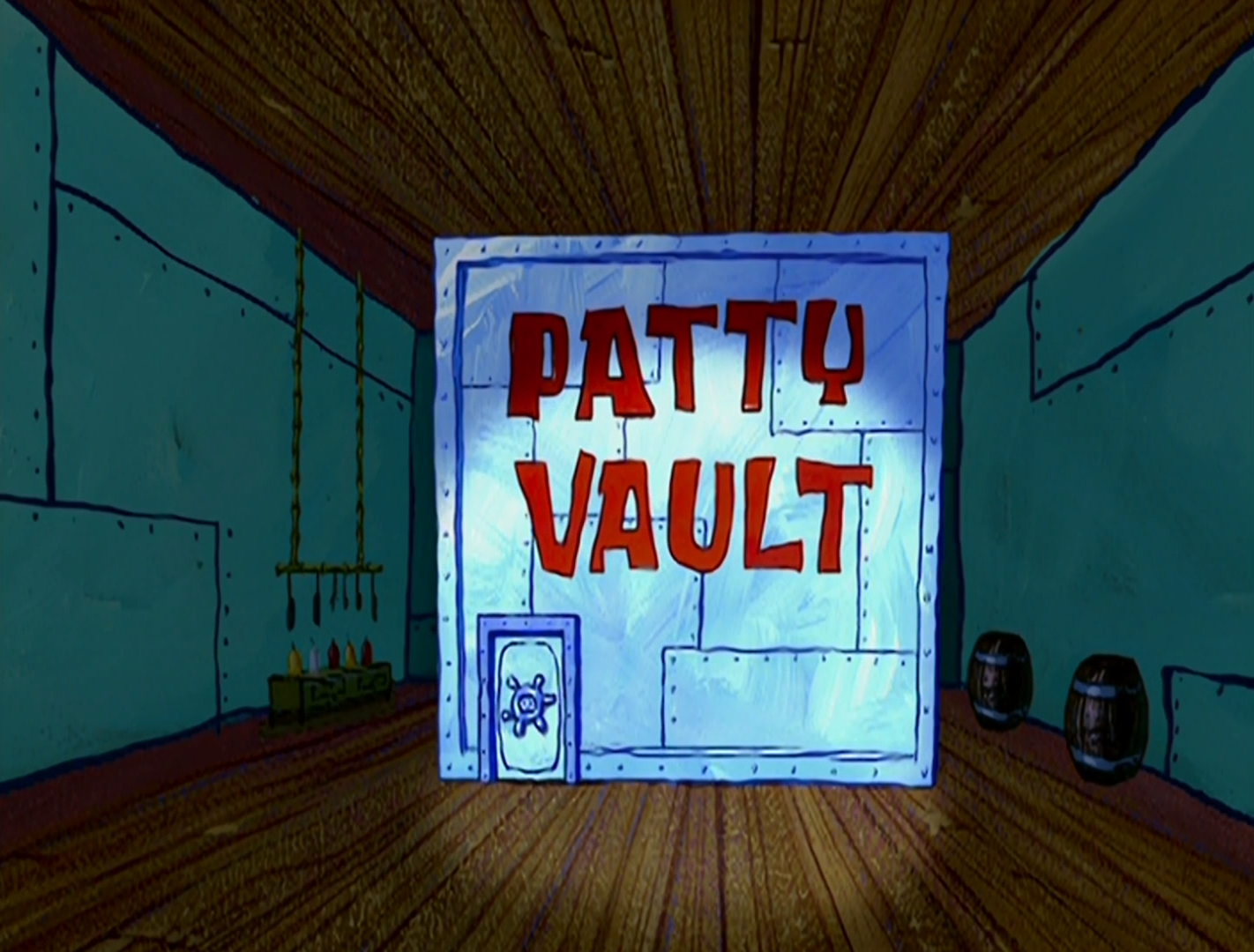

He sneaks out late at night and enters the Patty Vault.

He sneaks out late at night and enters the Patty Vault.

SpongeBob arrives on cue to ruin the moment for Squidward. While Squidward sweats and mutters, SpongeBob puts the pieces together: “You like Krabby Patties, don't you, Squidward?”

SpongeBob arrives on cue to ruin the moment for Squidward. While Squidward sweats and mutters, SpongeBob puts the pieces together: “You like Krabby Patties, don't you, Squidward?”

SpongeBob yells out warnings, and Squidward keeps on eating. Squidward finally stops, looks down, sees his thighs, and blows up.

SpongeBob yells out warnings, and Squidward keeps on eating. Squidward finally stops, looks down, sees his thighs, and blows up.

He ends up as a disembodied head, while a chuckling doctor holding his tentacles in a bucket says, “I remember MY first Krabby Patty.”

He ends up as a disembodied head, while a chuckling doctor holding his tentacles in a bucket says, “I remember MY first Krabby Patty.”

Squidward says, “Oh please. I have no soul,” and we see him in a chamber of hell.

Squidward says, “Oh please. I have no soul,” and we see him in a chamber of hell.

It's as if Squidward is being pressured to repent from the outside, which only makes him want to refuse more. Don Giovanni goes on being damned because the statue goes on twisting his arm. Squidward goes on refusing the Krabby Patty, although he loves it, because of all the people who want him to love it. But Squidward is too weak-willed not to repent, and it goes this way: first a private acceptance, then a confession to SpongeBob at the threshold of the sanctuary, (the Patty Vault), and finally a joyful entrance. But the twist is that he gets damned for repenting anyway!

It's as if Squidward is being pressured to repent from the outside, which only makes him want to refuse more. Don Giovanni goes on being damned because the statue goes on twisting his arm. Squidward goes on refusing the Krabby Patty, although he loves it, because of all the people who want him to love it. But Squidward is too weak-willed not to repent, and it goes this way: first a private acceptance, then a confession to SpongeBob at the threshold of the sanctuary, (the Patty Vault), and finally a joyful entrance. But the twist is that he gets damned for repenting anyway! Got that, Squidward? You're weird and different and you suck because your taste isn't normal. Fuck you.

Got that, Squidward? You're weird and different and you suck because your taste isn't normal. Fuck you.