I once worked with a doctor who spent the entire morning complaining about the cost of 30k Montessori preschool for his two kids, as well as unstated expenses for his part-time housekeeper. Fortunately, his wife is also a doctor, so with her second income they’re making an extra $120k, post-tax $80k, post preschool $20k, post housekeeper…let’s be generous and say $10k.

Stuff is cheap, people are expensive

I’ve got a few friends who went through business school, and as one might expect, they talk about success a lot. Not just how to succeed, in business, but what success looks like in modern society. When you break it down, people seem to have very different ideas of what success means – does it mean staying cashflow positive as a single person, supporting a family at an upper-middle class level, or kicking back on your private island? But one thing that everyone agrees on is that families are expensive.

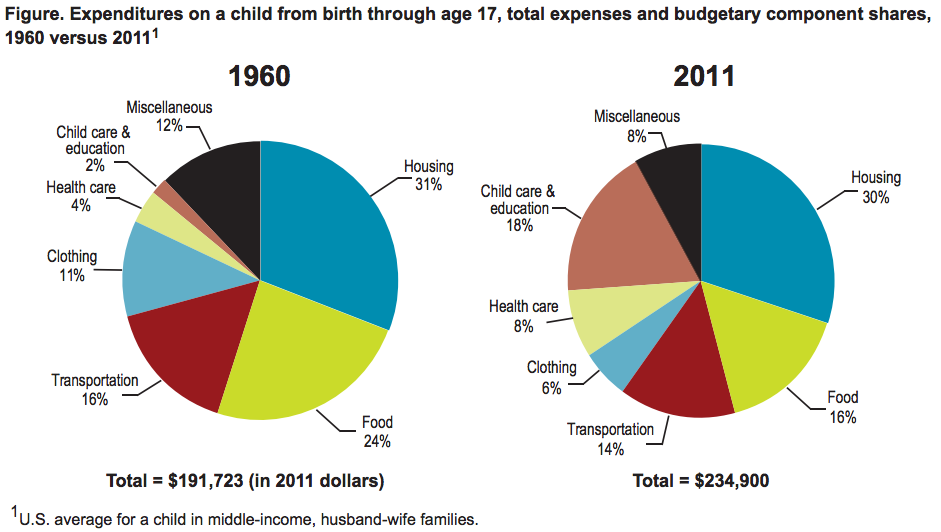

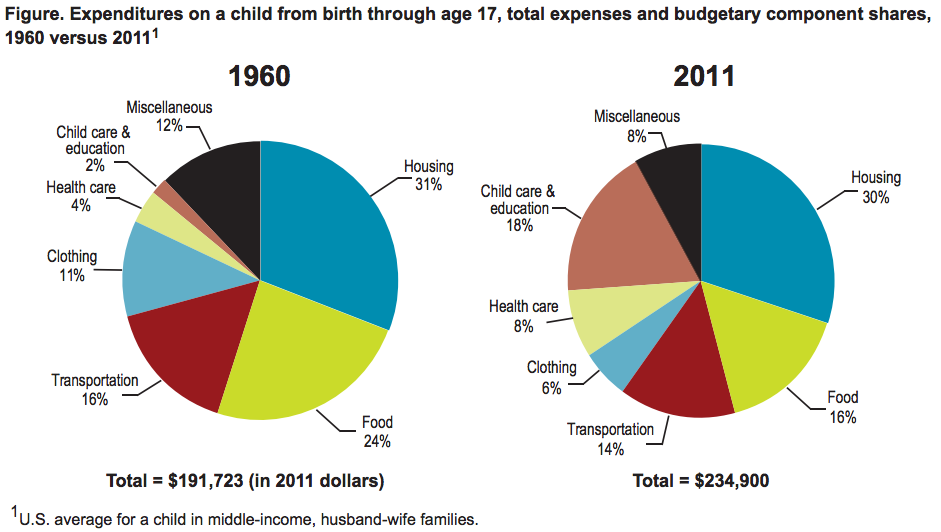

So why is that? Let’s take a look at a study breaking down the costs of raising a child in 1960 and today:

Material goods – food, clothing, and transportation – have gotten dramatically cheaper even as their quality has improved year on year. At the same time, the cost of healthcare and childcare/education have together more than quadrupled, and housing, the largest expense, has remained roughly constant.

The overall pattern here is that stuff is cheap, people are expensive. Wherever we’re buying a straightforward material good, with minimal change in social technology, things have gotten much cheaper in the past half-century. Clothing, which has almost halved in price, is probably the purest example.

But why have other categories gotten expensive? Well, healthcare is its own little bundle of brokenness, so let’s set that aside. Instead let’s look at childcare/education, which has shot up, and housing, which remains puzzlingly stagnant for what should be a product of physical technology, enjoying the same improvements as other material goods.

The increase in childcare expenses is largely driven by the rise of dual-earner households, childcare being part of the cost of working moms. (It’s worth noting that dual-earner households also probably prevented the decline in food expenses from being as dramatic as the decline in clothing expenses. Here, gains from technology and globalization are partly clawed back by greater reliance on prepared foods and eating out as women no longer have as much time to cook.)

Rising education expenditures are largely due to inflating college costs and increasingly mandatory college attendance, the results of higher education dysfunction and inefficient constraints on companies’ hiring practices that force them to rely on expensive credentials.

Housing costs are largely driven by zero-sum competition for good school districts and safe neighborhoods, which were in much greater supply in 1960. It’s true that houses have gotten larger, reflecting improved construction technology, so people are getting more house for their money. But part of the reason people are buying more house than they used to is that they’re using laws that indirectly discriminate against people you’d rather not have as neighbors, since the most effective ways to discriminate against bad neighbors have become infeasible. Minimum lot sizes, maximum occupancies, various environmental initiatives, and migration to exurbs all increase the amount of housing purchased. But people are buying more house not because they intrinsically like McMansions, but because what they’re buying is good neighbors and good peers for their children. Right now, McMansions are now the easiest way to do that.

In an age of globalization and continued improvement in material technology, it should be cheaper than ever to support a large family. But we end up giving up these gains and then some by having to throw cash at social technology failures, in a way that extends well past Baumol’s cost disease. The escalating cost of acceptable educations and houses in acceptable neighborhoods is not a fact baked into the universe, but a tax that we pay for dysfunction in the education and job market and our inability to maintain public cooperation without income-based segregation. More precisely, they represent a silent, unreported form of inflation.

The formal way to calculate inflation is to ask how much things cost, and track the prices over time. For potatoes and t-shirts, this formula works fine. By adding some mildly questionable but broadly accepted adjustments for changes in quality, you can even track the costs of cars and iPads over time. But when you’re looking at spending on social technology, this sort of robotic calculation breaks down. What people are buying with education is not a year of instruction in a Gothic building, it’s a credential that helps guarantee their employability. What people are buying with a house isn’t a pile of timber and concrete, it’s a space to live and raise children in a congenial environment. And these prices have been relentlessly increasing.

Two-income trap, one-income solution

Now, you can complain about these failures and push for political change. But it’s also entirely possible to solve them yourself by replacing these institutions at home and through local community. Parenting can replace daycare. Strong communities can replace ritzy housing. And homeschooling, either solo or in community, can replace schooling.

Now, to make this happen pretty much requires that one parent, almost always the woman, give up a traditional career track. This doesn’t preclude working. But it does mean the departing from the standard view of a life-fulfilling career that demands primary dedication and in exchange provides a narrative and social role for your life. Rather, she should treat work as a straightforward exchange of time and effort for money.

Doing this produces underappreciated benefits. For one, it can save a great deal of money; indeed, as our opening anecdote illustrates the “shadow housewife salary” can be very competitive with a market wage. One interesting thing about the housewife premium is that it scales almost linearly with class. While the opportunity cost for a high-income couple to give up the wife’s income is higher, so too are their expected domestic expenditures for things that a housewife can produce herself. For the average household, the shadow housewife wage is something on the order of cheap daycare, meal prep, and fixing inefficiencies at home, which can approach the median female pretax income of $40k. As the income scales up, you expect to spend more on things like housing, schooling, and maid service, and the housewife premium increases commensurately. If the family is willing to homeschool – admittedly a large step – they could also save on the real estate premium of good school districts, which in larger cities runs to several hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In many cases, too, home production is simply qualitatively superior to the market alternative. Parenting is better than daycare and local community is better than fancy neighborhoods, for the same reason that a nursing home is no substitute for a loving child taking care of her parents. And there are many other benefits besides these headline ones. Home cooking can be cheaper, healthier, and more personalized than eating out or precooked meals. Having a single person focused on making the home run smoothly can problem-solve and wring out efficiencies in ways that are simply impossible for two willpower-depleted employees.

Finally, a housewife can add value simply by not having a career that needs prioritization. In an age of multiple career jumps, two earnest careerists often can’t make the geographic moves that would be ideal for their careers – if, say, he’s a coder who’s best off in the Bay Area while her law firm has a plum opening in Atlanta. The job of a housewife, by contrast, is location independent, freeing up a single-income family to go all-in on optimizing that one income.

Indeed, there’s widespread vague desire for this sort of life – a life both more gracious and civilized, and one that empowers people to shape their home life to their liking, rather than being stuck with what life hands us as defaults. Reality show producers, fingers ever on the pulse of the collective id, have produced a proliferation of cooking shows and home makeover/fixer-upper shows. Interior decorating blogs and Pinterests abound. [1]

And it’s not only women who find a more domestically-oriented life preferable. Consider the dream of many tech workers: to have a “reasonable” ~10m exit from their company and not have to work again. From there, their dreams have a lot in common with the stereotypical housewife. They want to flexibly spend time with their family, devote energy to their hobbies, get involved in community projects, gossip groups. Now, their hobbies might be paleo dieting rather than crochet, their community projects might be nonprofits rather than PTAs, and their gossip groups might be angel investors rather than morning powerwalkers. But the outlines of this aspirational lifestyle remain the same.

And yet, a housewife’s lifestyle does not have to be aspirational. Martha Stewart may be one-of-a-kind, but any family can choose to live in a less-sprawling house, invest in community relationships, cook fresh meals at home, and look after their own kids. But, crucially, to make this work requires an entire cultural package and the community to support it.

Consider the example of the dual-doctor couple we started out with. There’s certainly no financial barrier to them reverting to one income. But nevertheless, the social barriers are high. They invested their youth in medical training, which means in practice that their social ties are primarily with other doctors, without a durable community outside the hospital. In this milieu, the wife would be taking a huge social hit upon becoming a housewife. Even though she’d have more free time to socialize, she’d miss most of the serendipitous social encounters that can be found only at work, and doesn’t know people outside work to compensate for it. Her working friends, at any rate, will be too busy working to meet up frequently.

And so, boredom. Running a household may have been a full-time job in 1900, but since the advent of dishwashers and washing machines, it’s no longer a full-time job. The ‘50s housewife had PTA meetings and groups of friends to fill her time; our doctor-housewife today largely no longer has these things. Churches and meetup groups do exist, but the sorts of professionals that end up as doctors and the like are precisely the sort of people who spent their youth grinding for the MCAT and not investing in them. To the extent that women are pressured to have it all, it’s far more dangerous to underinvest in your career, where your performance is measured quarterly and promotions are public, than in family, where consequences emerge years or decades later and dysfunction can be papered over for public view with a few professional Facebook photos.

Having been seeped in a culture where medical prowess (and more broadly, money and career) is the consensus status metric, it would also be a struggle for her to have an internal narrative of why what she does as a housewife is meaningful – something important both for other people to understand and for herself. The main thing keeping this couple in a dual-income household is the shackles of social poverty, not the lure of material success.

Elizabeth Warren talks about the two income trap, the idea that the middle class is still financially struggling despite having moved from one or two. She’s right on the description. Not only has GDP not doubled from doubling the number of workers, but declining social technology has actually increased the cost of having a family. But perhaps the answer is simple – not easy, but simple – the way out of the two income trap is to return to one income families. But to do that requires not only individual will but a community of families who can provide social ties, support one another, and provide an alternate narrative of the good life.

[1] While many women are indeed focused on career today, ambition is more flexible than you’d think. If the high-status thing for an adult woman was to be an excellent mother and a pillar of informal community institutions, we’d see lots of current happy career women happily pursuing a housewife’s lifestyle, just as the mainstream of Austen’s women were happily chasing pianoforte skills and marriages to wealthy men. In such a world, it’s entirely possible for a woman who legitimately loves a particular field of work (rather than the status we currently give to careers) to pursue advanced-amateur work in that area, but only the Emmy Noethers of the world would strongly desire to do so.