Free Speech and Gay Rights: ONE Inc. v. Olesen

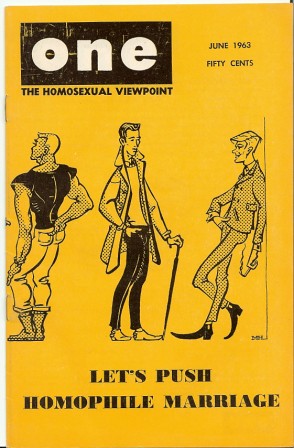

“june 1963” by Michael_Goff is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

On January 13, 1958 the Supreme Court of the United States gave the nascent gay rights movement its first major victory.1 In a brief decision in the case ONE Incorporated v. Olesen, Postmaster of Los Angeles, it declared merely “the petition for writ of certiorari is granted and the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is reversed. Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476.”2 With this sentence, the Court effectively ruled that discussions of homosexuality were not per se obscene and, implicitly, that such discussions might be protected under the First Amendment. Free speech had come out on the side of social justice.

The decision took place against the backdrop of the second Red Scare. Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, who has become synonymous with the hysteria around Soviet espionage, had been censured by the Senate four years earlier and had died the previous year. However, harassment, hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), firings, and blacklisting continued. These were targeted not just at suspected Communists, but also suspected homosexuals. Historian David K. Johnson has termed this the “Lavender Scare.”3 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director J. Edgar Hoover, politicians, and bureaucrats forced gay men in the federal government to quit their jobs, claiming that they posed a security risk. Psychologists generally considered being queer to be a mental disorder that had to be “cured.” Early gay rights groups, which at the time referred to themselves as homophile organizations, like the Mattachine Society, were few and had very limited membership. These groups relied on mail publications to communicate with members and to spread their message. However, postmasters around the country were empowered by obscenity laws to confiscate mail that was filthy or obscene – and this included discussions over homosexuality.

One group targeted by obscenity laws was ONE, Inc. A spin-off of the Mattachine Society created in 1953, ONE sent out a regular publication entitled ONE: The Homosexual Magazine.4 Otto K. Olesen, postmaster of Los Angeles at the time, objected to the content of the October 1954 issue and ordered it to be confiscated. ONE sued Olesen on two grounds. First, they argued that the publication was not obscene as Olesen claimed. Second, they argued that the “action of the defendant in refusing to transmit said magazine is arbitrary, capricious and an abuse of discretion, unsupported by evidence, deprives plaintiff of equal protection of the laws and constitutes a deprivation of plaintiff's property and liberty without due process of law.”5 The trial court was unconvinced, so ONE appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. In their decision, the Ninth Circuit spoke highly of free speech, saying:

At the outset it is well to dispel any thought that this court is its brothers keeper as to the type of reading to be indulged in. Since the advent of the printing press eminent scholars, including some men of the bench and bar, have uttered and written imperishable words in defense of the freedom of thought and expression, and the place of a free press in a free world. We need not take issue with this gallant host.6

They then promptly went on to take issue with that gallant host, declaring that the publication was obscene. Long judicial precedent had worked against ONE. Going back to the Comstock Laws of the 1870s, Congress and the courts had defined obscenity broadly. In their decision on One, the Ninth Circuit highlighted some of this precedent. The court ruled that obscenity had to be determined based on the effect that it had on the reader, rather than community standards broadly. You could determine if something was obscene if the material “depraved” their morals, “lead to impure purposes,” was related to “sexual impurity,” would “corrupt” their morals and more equally specific effects.6 These are manifestations of the Hicklin rule which declared something obscene on the basis of its ability to deprave or corrupt.7 Post offices empowered by statutes and court rulings that established these broad definitions censored a lot of material, political and artistic, between the 1870s and 1960s. They could censor books based on single paragraphs, rather than assessing the book as a whole. Moreover, obscene material, by definition, lacked any First Amendment protections whatsoever. Thus, when Olesen pulled the magazine, he did so on the basis of just a few stories he found objectionable.

One appealed to the Supreme Court at the best possible time. 1957 had been a surprisingly important year for free speech and obscenity. On “Red Monday,” June 17, 1957, the court put some brakes on the Red Scare with four decisions, including Yates v. United States that made it unconstitutional to arrest someone on the basis of what they convince others to believe, rather than what they convince others to do.8 Obscenity laws had been weakened in a series of legislative and legal actions. In 1930, Senator Bronson Cutting had succeeded in overturning a law that enabled the Customs Bureau to block books from entering the country on the basis of single passages. Now, they had to consider the book as a whole. Even more importantly was a case argued in April of 1957 – Roth v. United States. In this case, Samuel Roth, publisher of a magazine called American Aphrodite had been convicted of circulating obscene material. In their decision, the Court upheld his conviction, but they also narrowed the definition of obscenity by explicitly arguing that sex is not inherently obscene. They also ruled that obscenity would be determined not by the impact on an individual reader but through the application of community standards. Thus, the court continued the legacy of arguing that obscenity had no First Amendment protections, but limited the scope of what was considered obscene. It was this change in precedent that secured victory for ONE and for LGBT people across the country.

How important was free speech to ONE and in ONE? First, it is clear that a lack of free speech protections dramatically hurt the organization and the spread of its beliefs.9 In an article prior to ONE, the group’s legal counsel, Eric Julber, described the impact of censorship on them.10 The group was forced to self-censor in order to avoid criminal liability. It could not publish “lonely heart ads” – which greatly annoyed much of the readership – nor could it publish anything which might be construed as sexual or containing too much sexual content. Even with this self-induced censorship, ONE still had its publications confiscated.11 Julber recognized how important free speech was to the mission of the organization. “Though his high court victory garnered little attention at the time, Julber said he was proud of what he had accomplished. ‘I always thought it was a major case because it said homosexuals had a right to express their own views and a right to their own literature.’”12 Legal scholars agree with Julber. “USC law professor David Cruz said the ONE decision was most important not as a matter of legal doctrine but because of ‘Its on-the-ground effects.’ ‘By protecting ONE,’ he continued, ‘The Supreme Court facilitated the flourishing of a gay and lesbian culture and a sense of community at a time when the federal government was purging its ranks’ of suspected gays.”12 In the case itself, the short ruling cited Roth, indicating that the judges looked at the case through the lens of the First Amendment. Thus, once again, a social justice oriented group took on free speech as a practical cause to forward its social justice agenda. A legal precedent of broad free speech protections granted them victory in the courts, and removed a significant barrier to the success of the group.

1. Thanks to freedom-just-for-me.blogspot.com and gaynewsephemera.tumblr.com which had scanned copies of the trial court and Ninth Circuit court decisions, as well as some scans of ONE magazine (the ONE archive itself is not digitized). I wanted to include primary sources in this post, and I would not have been able to do so without them. For a sense of how the public views the case, you can see recent news coverage that mentions it, for example: https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-court-gay-magazine-20150111-story.html; https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/a-brief-history-of-gay-rights-at-the-supreme-court/; and https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/a-history-of-gay-rights-in-america/14/ 2. You can read this very short decision here: https://web.stanford.edu/~mrosenfe/more_cases/ONE_v_olesen_US_SC_1958.pdf 3. I highly recommend the book. David Johnson, The Lavender Scare. 4. You can learn more about the founding of the group here: https://one.usc.edu/about/history. In various places, their publication is referred to as ONE, One Magazine, ONE Magazine, or ONE: The Homosexual Magazine. For the sake of this post, I went with the final one because that is how the Ninth Circuit referred to it. 5. A copy of the first page of the trial court ruling (it was only two pages) can be found if you scroll through here: https://freedom-just-for-me.blogspot.com/search/label/One%20Inc%20v%20Olesen 6. Holding up free speech as an important value then promptly ignoring it is such a common theme in the history of the idea that it probably deserves its own book. You can read a transcript of the Ninth Circuit’s full opinion here: https://freedom-just-for-me.blogspot.com/p/241-f.html?m=0. Making transcripts is a pain so again I’d like to thank the blog. 7.Christopher Finan, From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act: A History of the Fight For Free Speech in America, page 197. 8. Christopher Finan, From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act: A History of the Fight For Free Speech in America, pages 166-67, 170, 195-98. I will note that Finan discusses ONE Inc. v. Olesen only very briefly, writing “the Court began to review the material that lower courts had declared obscene, including...a magazine for homosexuals.” (198). The brief mention here is likely because the case was not argued by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which is the emphasis of Finan’s book, and which turned down the opportunity to argue the case. See: https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-court-gay-magazine-20150111-story.html 9. Sometimes, folks argue that censorship is generally bad because it is ineffectual. It is ineffectual, they argue, because ultimately it just leads to a backlash where censored ideas gain more credibility and become more popular. As generally stated in public discourse (or at least as well as I can reconstruct – commentators leave this implicit) this is a bad argument and is generally not supported by historical evidence. Censorship can produce a backlash – the “Streisand Effect” – under certain circumstances (I’ll talk about them in a future post) but it does not necessarily produce a backlash. If it did, no one would ever have to argue against censorship because it would never work. I also have an hypothesis that the political ideology of the suppressed speech is very significant in whether or not its suppression leads to a backlash. In general, left-wing speech is easier to suppress than right-wing speech, because those adopting left-wing views tend to be marginalized from mainstream discourse. Now whether this is true everywhere at all times, I do not know yet, but to whet your appetite consider the case here. The Mattachine Society, Daughters of Bilitis, and ONE, Inc. were all quite moderate groups in comparison to modern LGBT rights groups. The aims of such groups were not even equal rights; all they asked for was a modicum of understanding of “social variants.” Yet, for the time, this was a radical view and supported in part by radical individuals like Harry Hay, a Communist who founded Mattachine Society. Thus, it was easy for postmasters, federal bureaucrats, and politicians to single them out and suppress their viewpoints. This suggests that censorship does work when it is targeted against marginalized groups making left-leaning arguments. This is a potential line of argument I intend to investigate further. 10. You can read his full article here: https://gaynewsephemera.tumblr.com/post/80910117486/one-magazine-october-1954-pages-4-5 11. One story that Olesen objected to, and which the courts agreed was obscene was “Sappho Remembered.” You can read this obscene story that includes no sex whatsoever here: https://gaynewsephemera.tumblr.com/search/One%20magazine 12. You can read Julber and Cruz’s comments here: https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-court-gay-magazine-20150111-story.html