The word “collapse” appears more and more often in recent political debate. Online, in the media, in the Academia, and in radical political circles, Collapse is gaining more and more visibility. Notably, the concept has yet to be claimed by a specific political party. Instead, Collapse has triggered a wide variety of voices from all over the political spectrum to participate in a discourse weaving politics, philosophy, different scientific disciplines, design, fiction, and technology.

This article is intended to be a simple introduction to orient oneself to understanding collapse: a topic that will necessarily become increasingly relevant in the years to come. It’s intended as a list of positions, factions, opinions, trends, coordinates of the debate, arguments on which the various oppositions hinge. There is no claim to exhaustiveness or historical depth: the roots of the current debate go back for centuries; even more difficult,new positions, new groups, new variations, new identities and definitions emerge on the daily. New agents proposing ideas on collapse come from every point of the political spectrum: they can be tracked to academic institutions,occult internet communities, to the most recent author who decides to address the issue and have their say. Mapping this disquiet by enumerating individual organizations, personalities, parties and communities is an exercise as challenging as it is fruitless.

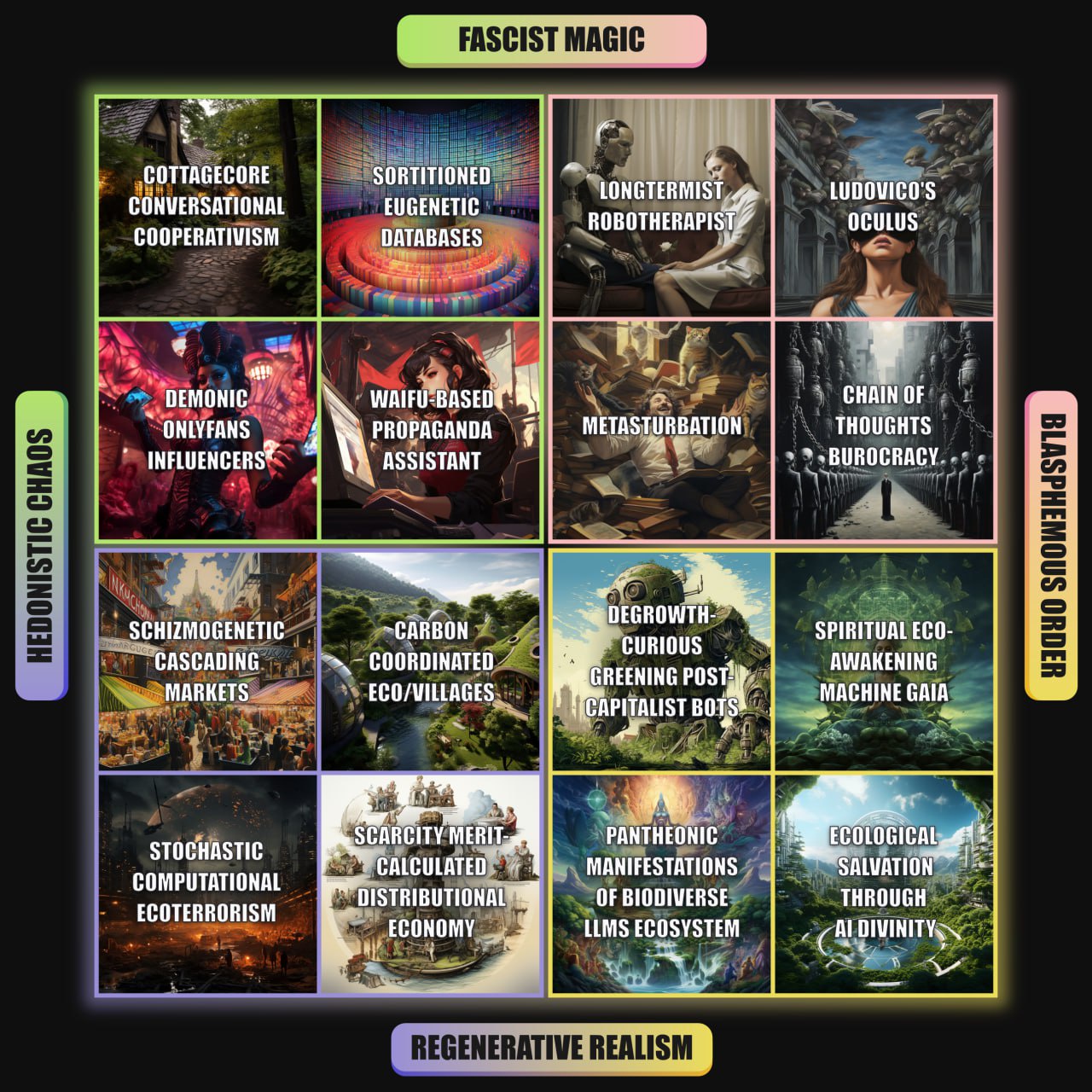

Instead, I believe it is much more interesting to provide simple interpretative tools to navigate this complex and fragmented debate. To do so, I will make use of a series of categorizations –some formulated by the very promoters of the positions presented here; others my own supplementation– to group together elements and actors that share common traits, influences and relationships. I hope the result won't resemble too closely the rigid taxonomies of nineteenth century anthropologists.

Before I begin, however, it is perhaps useful to summarize what is meant here by the term “collapse.” A precise definition is difficult, not least because it would mean taking sides in a debate in which there are quite divergent voices about what collapse is and how it will unravel. However, I hope not to be too biased if in this context I define collapse as the historical process of transition away from the complex, globalized, highly-connected and materially-abundant human society(ies). The result of such process would be a state of greater precariousness, lesser abundance and stability, potentially reaching a stage of existential risk for our species. Often, the Collapse is attributed to the mutual reinforcement of ecological, social, economic, and political instabilities already underway or irreversible in the near future.

Optimists

Radical deniers: there are no downward trends, climatic or ecological threats. The present order is not subject to threats of historic magnitude or capable of experiences compromised material and social well-being. Examples: Koch Brothers, Exxon, Clintel

Partial deniers: there are some downward trends; in particular problems of social inequality, economic instability or pollution. However, they are not sufficient to substantially change the reality in which we live. The economic-political system, humanity or other forces will inevitably correct these trajectories. The symptoms we observe are only temporary and destined to disappear.

Technological Optimists: collapse is possible, but it is a technical problem that can be solved. In particular, new technologies in the ecological, energetic, and digital field will be able to reverse the phenomena we are observing. Examples: Carbon capture advocates, The Climate Optimist

Economic optimists: collapse is possible, but can be prevented by encoding the right economic inputs to compensate for ecological externalities, inequalities, and social divisions. Social restructuring is not needed but better economic policy is.

Reformists: collapse will be prevented by deep restructuring of the production system, welfare, and huge investments in ecological remediation. There will be a political tipping point due to the damage caused by the approaching collapse and the resistance of nation-states to act and protect the status quo. When that happens, sufficient forces will be released for radical interventions. Examples: Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, Greta Thumberg, Green New Deal

Millenarists: the collapse will happen, but it is a good thing and necessary to free humanity from the present degradation. The difficulties it creates will help divide the righteous from the wicked. Millenarian positions exist in various communities: from religious fundamentalists who see the coming collapse as a kind of biblical doomsday to ethnic supremacists who await social collapse to remove the obstacles that currently prevent them from exterminating ethnic groups outside of their own. Examples: fringe radical Protestant groups in the USA.

Right-wing Accelerationists/Dark Enlightenment: the collapse of humanity will happen, but it is a necessary evolutionary step to free Capitalism from the need to support the human community. Rooted primarily in the accelerationist views of philosophers such as Nick Land and blogger Curtis Guy Yarvin, variations of this thinking promote an approach to collapse as something necessary and to be actively facilitated. Examples: NRx and other alt-right environments.

Pessimists

Defeatists: the collapse is inevitable because we should have acted earlier. Now any technical and political solution is superfluous. Examples: r/collapse, climate blackpillers

Hedonistic Defeatists: the collapse is inevitable and we must spend these last years enjoying what we have instead of working for a change that would not bring any result.

Post-collapsists: the collapse is inevitable and therefore we must act now to build conceptual, technical, and social tools that will serve us during and after the collapse in order to minimize long-term consequences. Examples: CollapseOS

Delayers: collapse is inevitable and the primary goal is to slow it down in order to extend current conditions as much as possible, making it easier to get through the collapse, and to minimize the cost in terms of human lives. Examples: Extinction Rebellion, Pablo Servigne

Types of collapse

So far we have talked about collapse without detailing it. However, there are radically different, often opposing, and irreconcilable visions of how collapse might develop. Going into the technical, logistical, ecological, and social detail of the changes daily reality will undergo during the collapse is necessary to understand the ideas and projects that develop from these visions.

Rapid collapse/Preppers: collapse will happen rapidly on a global scale within a narrow timeframe. Lots of small local infrastructure failures, political instabilities, or extreme weather events will prevent a gradual transition. So those who want to survive must prepare to endure conditions deeply hostile to the maintenance or formation of any form of organized society.

Linear collapse: collapse will occur slowly and globally. Global infrastructure and production chains will be increasingly harder to maintain. Many nation-states and local communities will see their material conditions deteriorate over the years, possibly without ever politically framing them as a consequence of global collapse but just as local problems with local causes. Although this will lead to a reduction in population and welfare, the gradual transition will allow for adaptation in every aspect of life in all those locations not affected by the worst effects of collapse.

Accelerated/non-linear collapse: due to ecological (e.g., methane release from permafrost) and infrastructural (e.g., fragility of the electronics production chain) cross-dependencies, there will be a breaking point where several different and converging forces will be triggered. These will accelerate collapse before a stable situation is reached. This rate of change may be too rapid for humans to adapt to effectively.

Ideologies

Just as different material visions of collapse produce different expectations, the ideologies are also intertwined with positioning oneself in the debate. Understanding new ideologies, existing ideologies, or their adaptations is a key lens for understanding the debate about the future. It is interesting to note how many ideologies, especially conservative and liberal, are incapable of considering regression as a possibility. They are therefore either absent from the discourse or present with denialist positions.

I have excluded all ecological political ideologies that do not conceptualize or express explicit positions on collapse as intended in this article, despite having some idea of ecological collapse or degradation as part of their thinking.

Eco-fascism: collapse is the fault of overpopulation, excess wealth, or the choices of particular nations or demographic groups. Restrictive measures, suppression of certain freedoms for a portion of the population or their physical elimination are necessary to avoid a global collapse.

Degrowth: an economic and social model that requires continuous growth, based on the predatory extraction of resources is unsustainable in the long run. New economic models are needed that are not constrained by the growth imperative. A more local production system with reduced cross-dependencies is needed to address the fragility of the current one, This local production system should anticipate the needs that will be imposed by the Collapse.

Eco-socialism: the State or an equivalent entity such as a confederation of communities must promote ecological balance and restructure society and productive systems to prevent or survive the collapse. Given the seriousness of the threat, the ecological issue must be fully integrated into political planning to maintain the material well-being achieved thus far.

Communalists/Eco-anarchism: the way to survive collapse is to build self-sufficient networks and communities capable of surviving and adapting to social and climate change, progressively eliminating dependencies on global and regional supply chains.

Aesthetics

When it comes to imagining the future, aesthetics are just as important as theory, if not more so. Given the impossibility of accurately predicting the complex evolution that will take place in the next decades and how it will affect every single aspect of everyday life, reasoning about possible worlds from an artistic, narrative, emotional point of view allows us to understand ourselves and mobilize people to action much more easily than a dry scientific report or an overly abstract theoretical treatise.

The theme has long been explored from different perspectives, often even before the possibility of a collapse became as concrete and close in time as it is now. Intentionally or not, literary, cinematic and artistic currents condition the discourse and determine what we imagine when we close our eyes and think about what our lives will be like in 50 years.

Post-apocalypse: the collapse will be rapid and violent, due to cataclysms on a global scale. What will follow will be a world of scarcity and deteriorating institutions. Factions will be in constant conflict with each other over the few resources available. Alternatively, the demographic collapse will be so profound as to reduce the density of human presence to the point where very small groups will be able to live on subsistence as nomads or in settlements. Examples: Mad Max, Fallout, The Survivalist.

Cyberpunk/Sci-fi: The social and ecological collapse is not accompanied by a reduction in material well-being or technological competence, but by a disproportionate growth of the gap between social classes. Often a collapse of the established order is not followed by a chaotic and violent conflict, but by corporations that replace the state and implement dystopian societies. Examples: Autonomous, The Peripheral, Elysium.

Solarpunk: the collapse of old social and productive structures is a positive mechanism capable of triggering a profound revolution in human societies. Under the threat of extinction, a social reconfiguration takes place that fully incorporates ecology, cooperation, and radically sustainable development. The result is a society capable of reproducing itself without destroying and without oppressing. Examples: The Dispossessed, Ecotopia, Sunvault.

Corporate Marketing: the collapse is characterized as a consequence of wrong consumer choices, focused on the use of “unclean” materials and products. The collapse is never represented directly, but hinted at and implied. The veiled hint towards collapse pushes the customer to purchase. Such approach does not prevent giving it specific traits, albeit weak and functional exclusively to the generation of profit. This aesthetic is mainly used in advertising, brochures, social media posts, and corporate communication in general.

Cottage-core: the fetishization of bucolic and isolated life is once again proposed by cottage-core as an escape from declining modernity. Collapse is seen as something distant that cannot reach the idyllic bubble. A strong dichotomy between humanity and nature poses the latter and contact with it as an escape route from present and future problems.

*If you have any suggestion to expand the list, corrections or comments on some of the positions presented that, I realize, risk not doing justice to the complexity of the thought and the communities behind it, you can reach me at my email address: simone.robutti@protonmail.com. I am very open to evolve this article in a collaborative way.

Strike of the Tech Sector in Milan, Italy, 1977. Detail of workers from Fimi-Phonola

Strike of the Tech Sector in Milan, Italy, 1977. Detail of workers from Fimi-Phonola