by Darius Kazemi, Feb 2 2019

In 2019 I'm reading one RFC a day in chronological order starting from the very first one. More on this project here. There is a table of contents for all my RFC posts.

New concepts for the network

RFC-33 is a big one. It's authored by Steve Crocker, Steve Carr, and Vint Cerf, although Crocker is the only author listed in the normative RFC listings. It's dated Feb 12, 1970 and is a preview of a paper that will be presented at the Spring Joint Computer Conference in May of that year. This RFC is yet another update to Déloche's RFC-11. It's titled “New HOST-HOST Protocol”.

The technical content

The introduction describes ARPANET for the uninitiated. I lays out that ARPANET is the first major computer networking attempt to connect computers using different hardware and different operating systems. I think this sentence is the shortest and best description of the network I've seen in an RFC so far:

The network is seen as a set of data entry and exit points into which individual computers insert messages destined for another (or the same) computer, and from which such messages emerge.

We get firm definitions of HOST, IMP, message, and link that are meant for outsiders. Since we as modern readers are outsiders, this is super helpful to us. We've already established firmly via these RFCs that a HOST is a computer connected to the network, and the IMP is a kind of early router-type device that does the packet switching.

A message is defined in this paper as

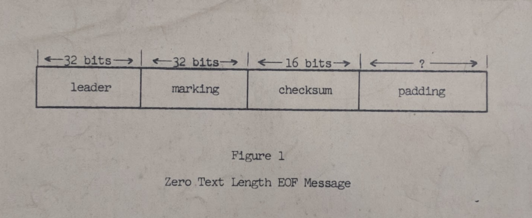

a bit stream less than 8096 bits long which is given to an IMP by a HOST for transmission to another HOST. The first 32 bits of the message are the leader.

The “leader” is what we'd call a “header” today and consists of

- the ID of the intended destination computer

- message type (there are two: normal messages, and an RFNM (request for next message), is a way of not overloading the network with too much traffic. The RFNM is sent by a receiving computer and is a way of saying “I got your message and processed it, please send me more data now”.

- some flags (bits that indicate whether a certain thing is true or false) for special cases that aren't covered in the paper

- the link number this message is to be sent over

A link is, basically, a single data communication channel that can be used by an IMP or a HOST. There are 256 of them on the network.

The paper defines a design philosophy which is pithy enough that I won't quote it here (it's the section “Design Concepts” beginning at the bottom of page 4 of RFC-33) but to sum up:

- HOSTs are expected to mostly do their own thing; the primary use of a HOST is not expected to be “connecting to ARPANET”, it will probably have its own local uses

- HOSTs are time-shared computers (that is, shared between multiple users; in modern parlance it is a server that multiple users can log in to)

- as much work as possible is put on the HOST systems, since they are all going to have their own idiosyncrasies and it would be pointless to dictate how they should work in detail

- network use is going to consist of prolonged conversations between HOSTs moreso than one-off data transfers

The main purpose of RFC-33 is to introduce concepts that are a result of those design considerations: “connections, a Network Control Program, a control link, control commands, sockets, and virtual nets.”

A connection is a formal way of piping the output of a process on one HOST to the input of a process on another HOST. A “process” is essentially a running program. Connections only go one way (“the output of my program is the input of your program”) so for a back and forth conversation, two connections are needed.

The Network Control Program (NCP) is the program that acts as the broker between a HOST program and the network, and is used to start and stop connections.

A control link is a reserved link between two HOSTs where NCPs can handshake with one another before they begin setting up full connections on other links.

Since any HOST could be running its own operating system, and different operating systems have different internal identifiers for processes, we need to translate these processes into a common name space. This is called a socket and it says “user A on computer B would like to speak on this connection about what we are calling process Z”.

(There is a value in the socket specification called the “AEN” which stands for... wait for it... “another eight-bit number”.)

A virtual net is... well, I'm not really clear on that even after reading this document. But it seems to be a kind of fingerprint across multiple HOST systems where you can log in to, say four different computers, and have data piping back and forth between all four of them for different purposes. So like, calculate geometry on computer A but then pipe the calculations over to computer B to display it on a monitor. That kind of thing.

Further down, the term port is defined as an input/output path related to a specific process. One process can have many ports.

In a section called “Higher Level Protocol”, something called Network Interface Language (NIL) is proposed. Its purpose seems very similar to Decode-Encode Language (DEL), which I write about at length in my post about RFC-5, in that both languages were proposed to make highly interactive, rich networked applications possible. Both were not implemented.

Analysis

I'm breaking up this section for readability because there's a lot to say.

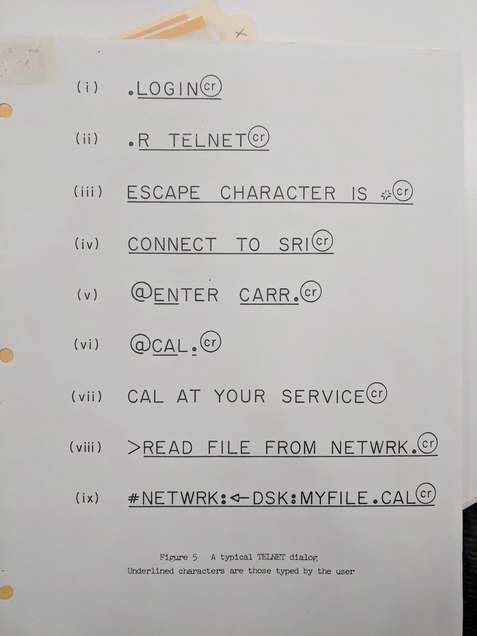

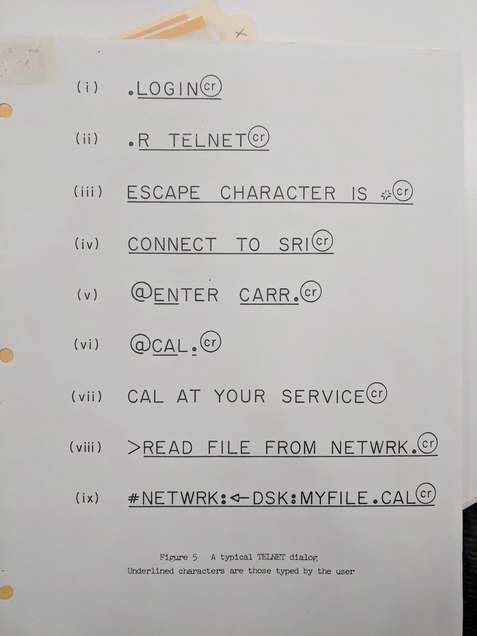

First of all, page 11 of the official normative RFC document references figure 5, which is missing. I found figure 5 when looking through some original documents at the Computer History Museum. Here is a photo I took:

You log in to the local computer, you start TELNET, you set your escape character, you instruct TELNET which computer to connect to, you enter your username on the remote computer, you start up a program on the remote computer, and you move resultant files from that computer to your local one.

TELNET gets a shout out

In a section outlining user-facing software, the document recommends that early ARPANET users use TELNET (as first defined in RFC-15) as a way to get an interactive login on remote systems, but notes that it's “expected that more sophisticated subsystems will be developed in time”.

The document credits TELNET for being the main reason why the network is currently useful at all.

Deep understanding of user experience

I was struck by this statement:

a user evaluates an interactive system by comparing the speed of the system's responses with his own expectations. Sometimes a user feels that he has made only a minor request, so the response should be immediate; at other times he feels he has made a substantial request, and is therefore willing to wait for the response. Some interactive subsystems are especially pleasant to use because a great deal of work has gone into tailoring the responses to the user's expectations.

This demonstrates deep understanding of interactive systems design by twenty-something grad students in 1970 that I wish more developers possessed today.

The human factor

The introduction contains the following note:

We have found that, in the process of connecting machines and operating systems together, a great deal of rapport has been established between personnel at the various network node sites. The resulting mixture of ideas, discussions, disagreements, and resolutions has been highly refreshing and beneficial to all involved, and we regard the human interaction as a valuable by-product of the main effect.

The ARPANET project as a whole is really interesting to me because of this necessary cross-collaboration between military, private, and academic institutions. The RFC concept in general is of course a huge piece of this collaboration and examining how this kind of collaboration happens is the real reason I'm doing this project.

Further reading

The request-for-new-message is kind of an early ACK message, which is worth reading about.

The “virtual net” concept is credited to William Crowther, who five years from this time will go on to write Colossal Cave AKA Adventure, the first ever text adventure / interactive fiction game. Crowther worked on ARPANET while at BB&N. It's amazing to me, in a good way, that “helping literally invent the internet” is a minor diversion when discussing this man's legacy.

There's an excellent 2015 paper by Bradley Fidler and Amelia Acker (available free online) that goes into the history of sockets on the ARPANET and proposes that sockets are both a kind of infrastructure and metadata.

How to follow this blog

You can subscribe to this blog's RSS feed or if you're on a federated ActivityPub social network like Mastodon or Pleroma you can search for the user “@365-rfcs@write.as” and follow it there.

About me

I'm Darius Kazemi. I'm a Mozilla Fellow and I do a lot of work on the decentralized web with both ActivityPub and the Dat Project.