by Darius Kazemi, Jan 20 2019

In 2019 I'm reading one RFC a day in chronological order starting from the very first one. More on this project here. There is a table of contents for all my RFC posts.

ASCII

RFC-20 is another Vint Cerf RFC, dated October 16, 1969. This is 13 days before the first message will be sent over the ARPANET.

I've been waiting for this RFC. I love this RFC.

Technical content

This requires a bit of background before I get into the RFC itself.

Character encoding

This RFC is about character encoding, so, what's character encoding?

Well, computers store numbers. That's all they do. Everything on a computer, when you drill down deep enough, is a number stored in memory somewhere. And yet we use computers to deal with written text all the time. This means that somewhere in the computer there has to be an understanding that the letter “A” is this number, “q” is that number, and so on. That's all a “character encoding” is.

The problem with ARPANET is that there was no guarantee that the letter “A” on one computer would be represented by the same number on another computer. So without some kind of agreed upon standard, I could be sending “hello” to your computer, but your computer would read it as “ifmmp”.

ASCII is the agreed-upon standard. It is the “American Standard Code for Information Interchange”, and was formalized as an information encoding standard in 1963 (although first proposed in 1961). The reason for ASCII goes back to Morse Code and telegraphs. Morse Code only allowed for uppercase A through Z and the numbers 0 through 9. There wasn't even a “period” allowed, which is why old-timey telegraph messages look like this:

THIS IS THE FIRST SENTENCE STOP THIS IS THE SECOND SENTENCE STOP

People wanted lowercase letters. They wanted punctuation. This led to many, many newer standards. Telegraph standards led to teletype standards which ended up getting used by computers (since teletype was a primary input/output device for computers before monitors and keyboards).

By 1963 there were over 60 different encodings used by computers. ASCII was developed to provide a standard for this. President Johnson signed a memorandum saying US federal computers needed to use ASCII to communicate in 1968. Since ARPA was a military network, ASCII was the only real choice for the job. From the memorandum:

All computers and related equipment configurations brought into the Federal Government inventory on and after July 1, 1969, must have the capability to use the Standard Code for Information Interchange and the formats prescribed by the magnetic tape and paper tape standards when these media are used.

The original content

This document is actually just a single paragraph written by Cerf. The remainder of the document is an attachment of what is presumably the official ASCII standard.

The part that Cerf writes explains that they are using the 7-bit ASCII encoding, meaning an ASCII character on an 8-bit computer looks like this in binary:

0010 0000

That first bit on the far left is always 0 (although if you look at the PDF scan, there is a margin note that says it's always 1?? either way the number is ignored). We have to store the number in 8 bits of memory because it's an 8-bit computer, meaning the smallest amount of data we can work with is 8 binary bits. So the first '0' is just cruft. We only care about the remaining 7 bits on the right. This lets us represent 128 different characters because there are 128 different combination of 0's and 1's you can make with 7 bits.

Importantly, different computers have to follow this standard for what everything means except for special characters such as the end-of-line character. (More on this in the “Analysis” section.)

The remainder of the RFC is the attached ASCII standard.

The attached standard

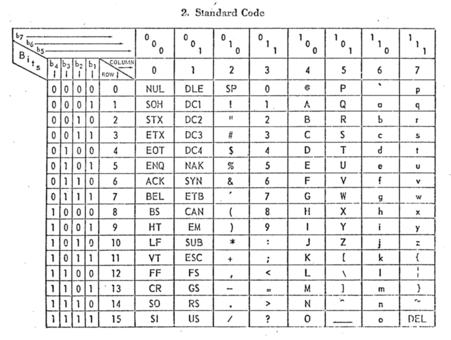

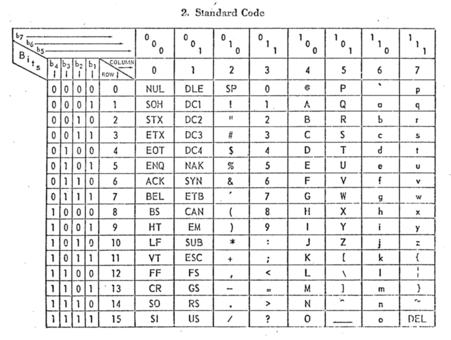

It's worth reading the scan of the document rather than the transcribed document that I link above, because the table is much clearer:

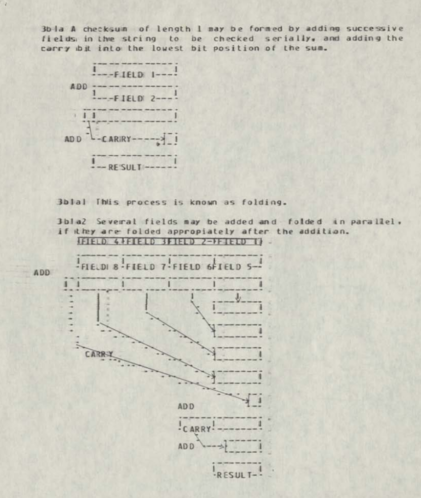

This table of values that says what number corresponds to what character. It's a little confusing at first because it doesn't just tell you the number straight away — in the interest of saving space and having it all printed out in a single sheet, it's a table where the columns represent the value of the first 3 binary bits and the rows are the last 4 binary bits. So the column labeled “100” and the row labeled “0110” give you 100 0110, which is the encoding for the letter capital “F”.

Interestingly, there is a pronunciation guide here! The anonymous government author takes care to note that ASCII is pronounced “AS-key” and USASCII as “you-SAS-key” (in the document itself an apostrophe is used to denote syllabic emphasis; I prefer caps).

Analysis

The choice of this encoding has made ASCII-compatible standards the language that computers use to communicate to this day.

Even casual internet users have probably encountered a URL with “%20” in it where there logically ought to be a space character. If we look at this RFC we see this:

Column/Row Symbol Name

2/0 SP Space (Normally Non-Printing)

Hey would you look at that! Column 2, row 0 (2,0; 20!) is what stands for “space”. When you see that “%20”, it's because of this RFC, which exists because of some bureaucratic decisions made in the 1950s and 1960s.

Remember that whole thing about a HOST providing custom definitions for stuff like its end-of-line character? If you are a computer programmer you've almost certainly hated having to deal with different end-of-line encodings in different operating systems and documents. Well, by my analysis you are pretty much looking at the source of your problems when you read this RFC. My condolences.

Further reading

The Wikipedia article for ASCII is pretty good. This Engineering and Technology History Wiki is better.

How to follow this blog

You can subscribe to this blog's RSS feed or if you're on a federated ActivityPub social network like Mastodon or Pleroma you can search for the user “@365-rfcs@write.as” and follow it there.

About me

I'm Darius Kazemi. I'm a Mozilla Fellow and I do a lot of work on the decentralized web with both ActivityPub and the Dat Project.