Which Quran?

Some Muslims may be surprised to learn that there are multiple variants of the Quran being recited today. Whilst something like 95% of the world’s Muslims adopt one recitation, there are at least three variants recited by the remainder, mostly in Northern and Central Africa. According to Traditionalism, all these variants, known as qirāʼāt, are valid and were all taught by the Messenger himself. This obviously contradicts the story most Muslims grow up with: that the Quran is one, revealed to the Messenger, preserved word for word, syllable for syllable.

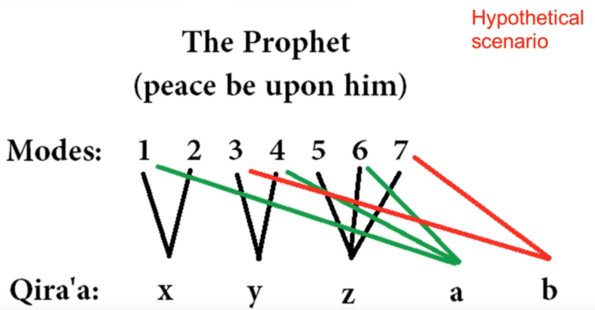

The author and vlogger Farid al-Bahraini gives an overview of the variant qirāʼāt in a short video [^1], and uses the following diagram to illustrate how they emerged:

So the variants of the Quran, the qirāʼāt, came from seven “modes” of the Quran. But what are these “modes”, or so-called aḥruf? The problem is, no one really knows. There are, according to Yasir Qadhi, up to forty different opinions on the matter [^2]. In his book An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur’aan, he suggests the correct opinion is that the seven aḥruf are seven different dialects the Quran was revealed in [^3]. He lists Quraysh, Ḥudhayl, Tamīm, Hawāzin, Thaqīl, Kinānah and Yaman as the seven, but then notes that “other scholars gave the names of other tribes.” [^4] Renowned Hanafi Jurist Taqi Usmani, in his book An Approach to the Qurānic Sciences, does list two different sets of tribal dialects, but then rejects the theory with the following. Why seven in particular, when there were many more Arabian dialects? [^5]

Another view that Qadhi details is the seven refer to the different ways verses can be changed. The list goes: change in wording; differences in wording or letters; change in word order; addition or subtraction of a letter or word; the form of the word structure is changed; differences in inflection points; differences in pronunciation. Qadhi argues that this opinion “seems to have the least weight…[and] does not really answer the question as to the meaning of the aḥruf.” [^6] However, Usmani thinks this is actually along the right lines and offers a scheme for the seven types of variations he believes to be correct: variation in numbers; variation in gender; variations in placement of diacritical marks; variation in verb; variation in syntax; variations caused by transposition; variations of pronunciation or accent. [^7] In responding to the likely objection that this view is conjectural and hypothetical, the Mufti points out that “this can be said of the opinions of all of them.” [^8]

In June 2020 Qadhi stated in a video interview that the standard narrative of Quran preservation with regards to the aḥruf and qirāʼāt “has holes in it”. [^9] His comments had inadvertently exposed how the laity had been kept at arm’s length from the issue because of the challenges in pinning down a coherent explanation. Given this, I was surprised to learn recently that opponents of Quranism are actually choosing to bring up aḥruf and qirāʼāt as a proof for Traditionalism. The argument goes that if you don’t believe in these vaguely worded hadiths and the range of contradictory opinions derived from them, then you have no way of knowing if the qirāʼāt in circulation today are all really from the Messenger!

I would argue that there is only one Quran, and the story of multiple recitations revealed by God or delivered by the Messenger, whether called aḥruf or qirāʼāt, are false. The one Quran is the one recited almost universally. Any variants which differ in wording to this one, whether recited today or in history, are deviations. We can know this by making a few simple observations.

To begin with, the Quran is a mass recited and memorised text. For Muslims, this process is institutionalised, which is one example of the devotion Muslims have for the Quran. We can also note that this devotion is not a modern innovation – we know Muslims historically have been memorising the Quran. From this we can move on to a second set of observations. Muslims also have historically been divided on many major issues. Hadith literature, for example. If one were to even take a cursory look at the development of hadith texts within Sunniism, it’s apparent the process of canonisation was highly contested. Furthermore, the Sunni and Shia groups have their own respective collections, with entirely different methodologies for authentication and application. The emergence and distribution of schools of theology and jurisprudence can be characterised in similar terms.

This is entirely expected and normal for a civilisation spanning over a thousand years and multiple continents. These divisions happened organically, and certainly not borne of a controlled process. What’s more, we can also observe that Muslims have shown devotion to their respective groups within these divisions. Sunnis and Shia on the whole have not abandoned their own team in favour of the other. Adherents of the different schools of fiqh have also held to their respective positions. And so on.

This second set of observations gives us a useful point of reference when considering the transmission of the Quran. We know that the canonisation of the Quran was under control from the very beginning, because if it wasn’t, it would have had a variation and spread like hadith texts. If there really were seven versions of the Quran, or ten variant recitals, one recitation could not have reached 95% adoption. Because if all the readings were divine as Traditionalists claim, the devotion and dedication shown by Muslims today to the Quran must have extended to all the variants from the beginning. There is no scenario where Muslims reciting a variant Quran would have abandoned their recitation in favour of a different one. We know this because, as already mentioned, Muslims of different groups have refused to abandon their camps in lesser matters.

In short, the recitation of 95% of the world’s Muslims is the preserved Quran. This is a manifestation of al-dhik’ri l-marfūʿ, the most elevated remembrance, which is how the Quran describes itself in ʿabasa⋆80/14. It is not a coincidence or an accident of history that Muslims would converge on one recitation in this way.

As a final point, there is no evidence from the Quran that God revealed it as a multiform text. In fact, it repeatedly refers to itself in the singular form dhik’r. And one last quote from Yasir Qadhi on the strength of evidence available to Sunnis: “…there does not exist any explicit narration from the Prophet, or the salaf concerning the aḥruf: these various opinions are merely the conclusions of later scholars, based upon their examination of the evidences and their personal reasoning (ijtihaad).” [^10] Traditionalists who push the seven aḥruf stories are on dangerous ground – it is no trivial matter to attribute actions to God without evidence. The Quran says in al-isrā⋆17/36, “And do not pursue that of which you have no knowledge. Indeed, the hearing, the sight and the heart – about all those (one) will be questioned.” And al-nūr⋆24/15 says, “…when you cast it with your tongues and say with your mouths that which you have no knowledge of, and you consider it insignificant, but with God it is immense.”

◆◆

Tagged: #ahruf #qiraat #quran-preservation

Notes:

[^1]: al-Bahraini, F. [Farid Responds]. (2020, June 29). Are the Qiraat mistakes? [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K11XfOfTFAU [^2]: Qadhi, Y. (1999). An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur’aan. (p.175). Birmingham, UK: Al-Hidaayah Publishing and Distribution. [^3]: Ibid. p.179 [^4]: Ibid. p.177 [^5]: Usmani, M.T. (2000). An Approach to the Qurānic Sciences. (p.109). Pakistan, Karachi: Darul-Ishaat. [^6]: Qadhi, p.178 [^7]: Usmani p.114 [^8]: Usmani p.123 [^9]: Wikimedia Foundation. (2025, April 29). Yasir Qadhi. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yasir_Qadhi [^10]: Qadhi p.176