Evollaqi on natural reading

“A common argument Qur'anis make is that “obey the Messenger” only means 'obey the Message he brought', which means 'only obey the Qur'an'. Or that when we're told to have the Prophet adjudicate our affairs and listen to his instructions, he is only going to adjudicate and instruct based on the Qur'an. Or when we're told to follow the Prophet, this just means follow the Qur'an (as that's only what he's brought and that only what he's living and teaching). Or that purifying us, teaching the wisdom, and other things the Messenger is instructed to do are all just different aspects of giving us the Qur'an, nothing further.

In response one could say, sure, this is all linguistically possible, but it's always possible to say that a reference to a term A is in in fact always exclusively a reference to a term B, as term A is only meant qua term B. B-aloneism is always linguistically possible.

To illustrate this, we could be Sunnah aloneists and read everything in the Qur'an accordingly. We could say “obey God” in the Qur'an exclusively means 'obey the teachings and practices of the human He told us to obey', “follow the Book” doesn't mean 'follow the Book per se' but 'follow the human it grants authority to', and so on. This would be an implausible reading, albeit linguistically possible. And that's the point. A more natural reading of a text we believe is word-for-word perfect and from God is that means what it apparently says, rather than using a number of convoluted synonyms, and adding superfluous words, and leaving out words which would be needed to specify a general statement. The Qur'an doesn't only say obey the Qur'an but “obey God and the Messenger” – suggesting two different sources of speech to be obeyed.”

This was part of a much longer thread going through the arguments for the classical Sunni doctrine. I felt like commenting on this specific point about natural reading. The argument is that to read “obey God and His Messenger” as one obedience is not the natural way to read it, and while linguistically possible, is implausible.

One way to assess this claim is to think about al-tawbah, 9/3:

๏ And an announcement [adhānun] from God and His Messenger to mankind (on the) day of al-ḥaji l-akbar: that God is disassociated of al-mush'rikīn and (so) is His Messenger. So if you repent, then it is good for you. But if you turn away then know that you never escape God. And give tidings of a painful punishment to those who conceal. ๏

Notice that there is only one announcement, adhān, yet it is said to come from God and His Messenger. If the explicit mention of God and His Messenger “suggest[s] two different sources of speech to be obeyed,” how do we understand one adhān coming from them both? Did they make the adhān in unison? Or were they co-authors of the announcement?

No one interprets it like this because the natural reading is that the announcement is God’s and His Messenger delivered it. And I don'’t know of any commentators who thought this phrasing was even worth explaining. So what Evollaqi dismisses an implausible reading is the most natural one here – and arguably any alternative would be implausible. This is evident again in al-anfāl, 8/20:

๏ O you who have believed! Obey God and His Messenger and do not turn away from him [ʿanhu] while you hear. ๏

Traditionists believe it is possible to obey the speech of God but disobey the speech of the Messenger, however, the above verse doesn't seem to see it that way. It identifies both God’s as well as His Messenger’s obedience but ends in the singular pronoun, and not a dual one – “and do not turn back from him while you hear”. The pronoun in the singular is for the Messenger to whom the Believers are asked to listen to attentively.

A final thought about this part:

“A more natural reading of a text we believe is word-for-word perfect and from God is that means what it apparently says, rather than using a number of convoluted synonyms, and adding superfluous words, and leaving out words which would be needed to specify a general statement.”

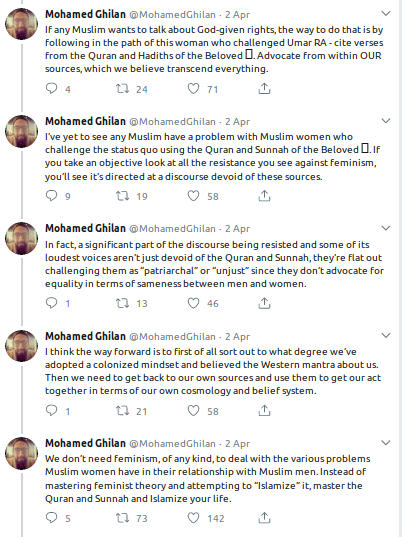

As is typical in these sorts of polemics, people seem to lose track of their own arguments. Further down the thread, Evollaqi says:

“When the Qur'an says it is enough, in context what it is saying is that it is enough as a miracle – ie that it is enough to evidence the truthfulness of the Prophet saw. He doesn't need to part waters or restore sight to the blind to establish he should be followed.”

So what happened to the text means what it apparently says? The Quran never says it is “enough as a miracle” but it does say its qaṣaṣ are “a detailed explanation [tafṣīla] of all things [kulli shayin] and a guidance and mercy for a people who believe” (yūsuf, 12/111). If contextual reading allows Sunnis to opt for interpretations other than the most apparent meanings of the text, perhaps this is something others are allowed to do too?

Obviously none of this is actually about the language of the Quran. It’s more than just plausible to take ”obey God and His Messenger” as a single obedience, but this reading undermines traditional doctrine – which is what’s really at stake here.

◆◆

Tagged: #quranism #tradition #quran