“A word about feminism and the notion that the type of it being advocated by Muslim women is one that advocates for getting their God-given rights. […]

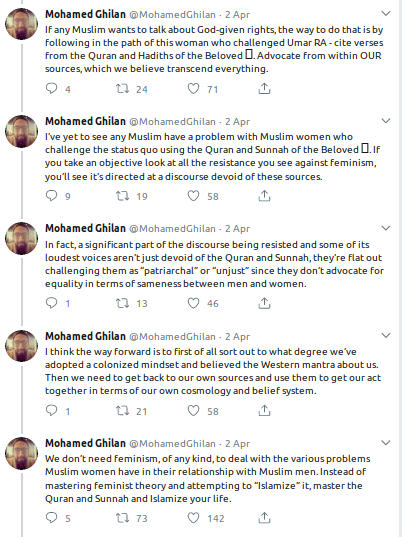

If any Muslim wants to talk about God-given rights, the way to do that is by…cit[ing] verses from the Quran and Hadiths of the Beloved ﷺ. Advocate from within OUR sources, which we believe transcend everything. I’ve yet to see any Muslim have a problem with Muslim women who challenge the status quo using the Quran and Sunnah of the Beloved ﷺ. If you take an objective look at all the resistance you see against feminism, you’ll see it’s directed at a discourse devoid of these sources. In fact, a significant part of the discourse being resisted and some of its loudest voices aren’t just devoid of the Quran and Sunnah, they’re flat out challenging them as “patriarchal” or “unjust” since they don’t advocate for equality in terms of sameness between men and women.

I think the way forward is to first of all sort out to what degree we’ve adopted a colonized mindset and believed the Western mantra about us. Then we need to get back to our own sources and use them to get our act together in terms of our own cosmology and belief system. We don’t need feminism, of any kind, to deal with the various problems Muslim women have in their relationship with Muslim men. Instead of mastering feminist theory and attempting to “Islamize” it, master the Quran and Sunnah and Islamize your life.” x

This was interesting to me only because of who said it. Mohamed Ghilan is a vegan.

He states his case for veganism in this essay. In brief, he argues that today’s mass meat consumption and capitalism-driven consumerism inflicts widespread cruelty upon animals, and is causing environmental degradation across the planet. Veganism addresses this, and so its adoption is not merely a good but a “Sunnah imperative.” To realise the ethics of Islam to its fullest, we should take the examples of what the Prophet did from the texts and build on them to deal with contemporary problems by asking: “What would the Habeeb do?” So while veganism has no precedence in Islamic history, it is entirely within the spirit of the Sunnah.

For me, this invites the question, how does a person who “Islamized” veganism in this way tell other Muslims to make no attempt to do the same with feminism?

Dr. Ghilan’s call to Muslims to go back to their sources instead of looking to feminism is similar to reactions to his own veganism-as-Sunnah position. Some readers pointed out that the Prophet consumed meat and that if Muslims are to pursue environmental activism, it should be through implementing the Sunnah as per the classical texts, not by looking to secular politics for guidance. In a follow-up podcast, Dr. Ghilan responds to this point directly:

“I included in the article relevant Hadiths on Al Habeeb ﷺ’s eating habits, and for the brothers and sisters who were so quick to point out that he ﷺ loved shoulder meat from sheep I have to ask a question: given that part of Al Habeeb ﷺ’s diet was to sometimes not have meat for weeks at a time, and this was done deliberately on his part as Lady Aisha RA stated, when was the last time you could say you haven’t had meat for a few weeks? In fact, most of us have meat not once, but at least twice per day on a regular basis. If we were really trying to champion the Sunnah in our diets, we wouldn’t selectively quote Hadiths about what type of meat the Beloved ﷺ loved most. Rather than abusing the Sunnah to justify our gluttony, we would use the Sunnah and fast Mondays and Thursdays; we would deliberately go hungry sometimes without needing to; we would eat only few morsels of food to keep our backs straight; and we would at the very least be following a semi-vegetarian diet where we abstain from consuming meat for a few weeks at a time. This right here is the bare minimum application of the Sunnah, where we concern ourselves with only ourselves, and not take into account the interconnectedness of the world in which we find ourselves living in.”

It’s not difficult to see how this line of reasoning might apply to conversations around sex-group dynamics as well. Do men who cite the textual sources to oppose feminism treat and engage with women in the way the Prophet did? Do they actually champion the Sunnah, or is the Sunnah cited as a way to shut women down and maintain the status quo? Muslim feminists can demonstrate without much difficulty how Muslim communities fail in “the bare minimum application of the Sunnah” in their treatment of women.

When it comes to the environmental agenda, one of the reasons Dr. Ghilan thinks veganism is justified is that the material conditions from the time of the Prophet have changed:

“But here’s the rub. Before the industrial revolution and the rise of modern cities, people lived organically as part of nature. There was an innate understanding and maintenance of balance. There was no production and distribution of food at industrial levels and a systematic hiding of how it impacts the Earth.”

The suggestion is that even if the majority of Muslims did apply the historical and text based Sunnah to their lives, it would not achieve the same balance with nature that the early Muslim community enjoyed. Fasting on Mondays and Thursdays at this point would have a limited impact on deforestation of the Amazon, so we must explore additional actions. And again, it should be obvious how this argument could work in other contexts. The objectification, sexualisation and pornification of women is a lucrative, global industry, a development of globalisation, unknown during the time of the Prophet. As is the sheer scale of the international trafficking of girls and women. And from figures gathered by UNICEF in 2014, “around 120 million girls worldwide (slightly more than 1 in 10) have experienced forced intercourse or other forced sexual acts at some point in their lives.” These realities represent a change, shift and intensification in the material conditions faced by girls and women from what was known in the times of the Prophet.

It might be that Dr. Ghilan doesn’t see the parallels, or doesn’t think there is a systemic element to female oppression in the way he understands to be the case with global environmental damage. Or maybe he does – his claim that Muslims do not need feminism “to deal with the various problems Muslim women have in their relationship with Muslim men,” seems carefully worded. It implies the problems Muslim women have with Muslim men can be separated and dealt with independently from wider problems that women have the world over. Even if this were the case, by his own admission Muslims must concern themselves with the balance the Divine intended for humankind, not just the balance between Muslims.

So we should be asking questions like, what would the Habeeb do if he knew that according to Amartyan Sen the killing of girls is the greatest act of murder in history. Sen estimated in the 90s that there was at least one hundred million women missing from the world. One hundred million – aborted before birth, killed in infancy, or dead through differential parental treatment, across the world.

None of this is to say that if you agree with veganism you must also agree with feminism. But, given the careful consideration Dr. Ghilan gives to a political movement with no Islamic precedence with the aim to tackle a structural problem that affects us all, you would think he would be more open and sympathetic to others who attempt the same.

◆◆

Tagged: #islam #mohamedghilan #feminism #sunnah