Apuntes sobre los desafíos de la violencia de género online inspirados por el financiamiento de Epstein a la ciencia y la tecnología.*

Por Paz Peña O.

Hay un elefante en la habitación. En ésta y en todas las habitaciones en Santiago o en otras ciudades de Chile y el mundo donde nos reunimos, cada tanto, a discutir sobre los diferentes matices de la violencia de género que ocurre bajo los soportes digitales. Hay un elefante invisible que apenas se deja sentir por los presentes y que con suerte nos libera espacio para nuestra presencia.

Como soy muy mala para improvisar y porque tampoco son tan comunes las oportunidades para hablar del tema y, por sobre todo, porque la fuerza de las últimas noticias demuestran elocuentemente los problemas inherentes de la industria digital dominante, quisiera tomarme unos minutos para hablarles de uno de los elefantes más importantes de la discusión mundial sobre violencia de género online.

Un elefante recorre Silicon Valley: es el fantasma de la misoginia.

En los últimos días, sendos reportajes en los medios escritos más importantes de Estados Unidos, han puesto en portada la estrecha relación que el mundo de la ciencia y la tecnología tuvo con el millonario Jeffrey Epstein.

Para las personas que no saben quién es este personaje, a mediados de este año, Epstein fue encarcelado y acusado por la fiscalía de Estados Unidos de gestionar una “vasta red” de mujeres menores de edad a las que presuntamente pagaba por servicios sexuales en sus mansiones de Manhattan y Florida. El modus operandi era que tres de sus empleados gestionaban sus encuentros sexuales con mujeres expresamente menores de edad, que provenían de hogares pobres o familias desestructuradas, las cuales eran contratadas para dar masajes pero que, pronto, terminaban siendo abusadas por Epstein y, a veces, por sus otros amigos millonarios.

Alrededor de 80 fueron los testimonios de mujeres recabados por la fiscalía. Epstein arriesgaba una pena de hasta 45 años pero, el 10 de agosto de este año, fue encontrado suicidado en su celda.

Ya en el 2008, Epstein había eludido los cargos federales por estos crímenes, gracias a un controversial acuerdo con la fiscalía, en el que aceptaba 13 meses de cárcel y ser inscrito en el registro federal de delincuentes sexuales.

Epstein financiaba de forma millonaria a científicos y centros de innovación y tecnología en Estados Unidos. De hecho, alguna vez dijo “solo tengo dos intereses: ciencia y coño” (haciendo una traducción al español castizo de science and pussy). Así, por ejemplo, era común que hiciera reuniones con científicos en su isla privada, como la que hizo sobre inteligencia artificial en el 2002.

Este financiamiento continuó en pleno 2008, cuando ya él mismo había reconocido ser un agresor sexual. Así, nos enteramos hace algunos días que el prestigioso MIT Media Lab del Instituto de Tecnología de Massachusetts, a través de su director Joi Ito, siguió recibiendo sus millonarias donaciones, con el forzado truco de hacerlas anónimas, además de invitarlo al campus (a pesar de su historial de agresor sexual) y consultarle del uso de los fondos.

Para las personas que no conocen el MIT Media Lab, recordar que es el laboratorio de diseño y nuevos medios fundado por Nicholas Negroponte, el mismo que creó luego ese programa marketinero que, entre colonialismo y tecnosolucionismo, buscaba brindar One Laptop Per Child. Para muchos el MIT Media Lab responde al brazo “académico” de Silicon Valley, que representa la denominada Tercera Cultura, la que busca juntar artistas, científicos, empresarios y políticos para crear humanidades con base científica.

Según los documentos obtenidos por el periodista del New Yorker, Ronan Farrow (sí, el mismo que destapó el escándalo de Harvey Weinstein que inició la ola #MeToo en Estados Unidos), Epstein sirvió como intermediario entre el MIT Media Lab y posibles donantes como el filántropo Bill Gates (sí, el de Microsoft) de quien aseguró USD 2 millones, y el inversor de capitales privados, Leon Black, de quien aceptó USD 5.5 millones. El esfuerzo por ocultar la identidad de Epstein era tal que Joi Ito se refería al financista como Voldemort, “el que no debe ser nombrado”.

Este escándalo en el MIT Media Lab ha llevado a que la discusión sea, increíblemente, sobre si la ciencia y la tecnología se puede o no financiar con dinero de fuentes “dudosas”. ¿Sobre las víctimas? Escuetas palabras de buena crianza. Porque de eso se trata el mundo Silicon Valley, finalmente: financiamiento por capitales de riesgo, un modelo que los centros de innovación como MIT Media Lab parecen aceptar sin chistar. El dinero al que mejor venda disrupción, innovación y todas esas cosas que se dicen en las Ted Talks.

Lawrence Lessig, amigo de Joi Ito, reconocido académico y creador de las licencias Creative Commons, escribió un largo artículo donde defiende a Ito -que alguna vez describió a Epstein diciendo que era “realmente fascinante”- diciendo que Joi Ito estaba convencido de que Epstein se había reformado y que era lo suficientemente brillante para darse cuenta de que podía perderlo todo. Más aún, Lessig supone que las donaciones de Epstein aceptadas por el MIT Media Lab no son un lavado de imagen para Epstein, pues Ito las forzó a ser anónimas.

En su largo artículo no hay ninguna reflexión por las mujeres menores de edad víctimas de Epstein porque, de repente para el mundo dominante de Silicon Valley y de su brazo académico, la única víctima de Epstein es Ito.

Recuerdo haber terminado esa columna de Lessig, académico cuya obra me introdujo al mundo de la cultura libre, totalmente pasmada. Evgeny Morozov, académico e investigador, describió mejor mi sentimiento en una columna:

“No es raro que lo intelectuales sirvan como idiotas útiles para los ricos y los poderosos, pero, bajo La Tercera Cultura, esto se lee como un requisito de trabajo”.

Meredith Whittaker, científica investigadora de la Universidad de Nueva York, cofundadora y codirectora del AI Now Institute, tuiteó a propósito de esta deriva en la conversación sobre Epstein y el MIT Media Lab algo muy significativo:

“Las contorsiones mentales de los #ChicosListos oficiales de la tecnología, usando párrafos para decir lo que se podría en una sola oración: que el abuso y la exclusión de mujeres y niñas es un daño colateral aceptable en la búsqueda de la INNOVACIÓN. La crisis de diversidad en la tecnología no es una sorpresa”.

Estas simples palabra son, justamente, el elefante en Silicon Valley que todo el mundo sabe pero que siempre es doloroso y decepcionante aceptar: los cuerpos de mujeres y niñas, la integridad de sus vidas como sujetos y como parte de comunidades, no importa.

No existen, ni siquiera en una discusión que las atañe directamente como la de Epstein. No está en la ecuación de la innovación, salvo como un add-on que se baja de “la nube” y que trata de parchar errores que cuestan salud mental, vidas y hasta democracias.

¿Que el modelo del engagement ha dado pie a intervenciones dirigidas en periodo de elecciones? Ups, pues hagamos otro algoritmo que lo resuelva.

¿Que las decisiones de los sistemas de inteligencia artificial pueden perjudicar más a personas por raza y clase social? Ups, nos reuniremos en San Francisco a hacer unos principios éticos.

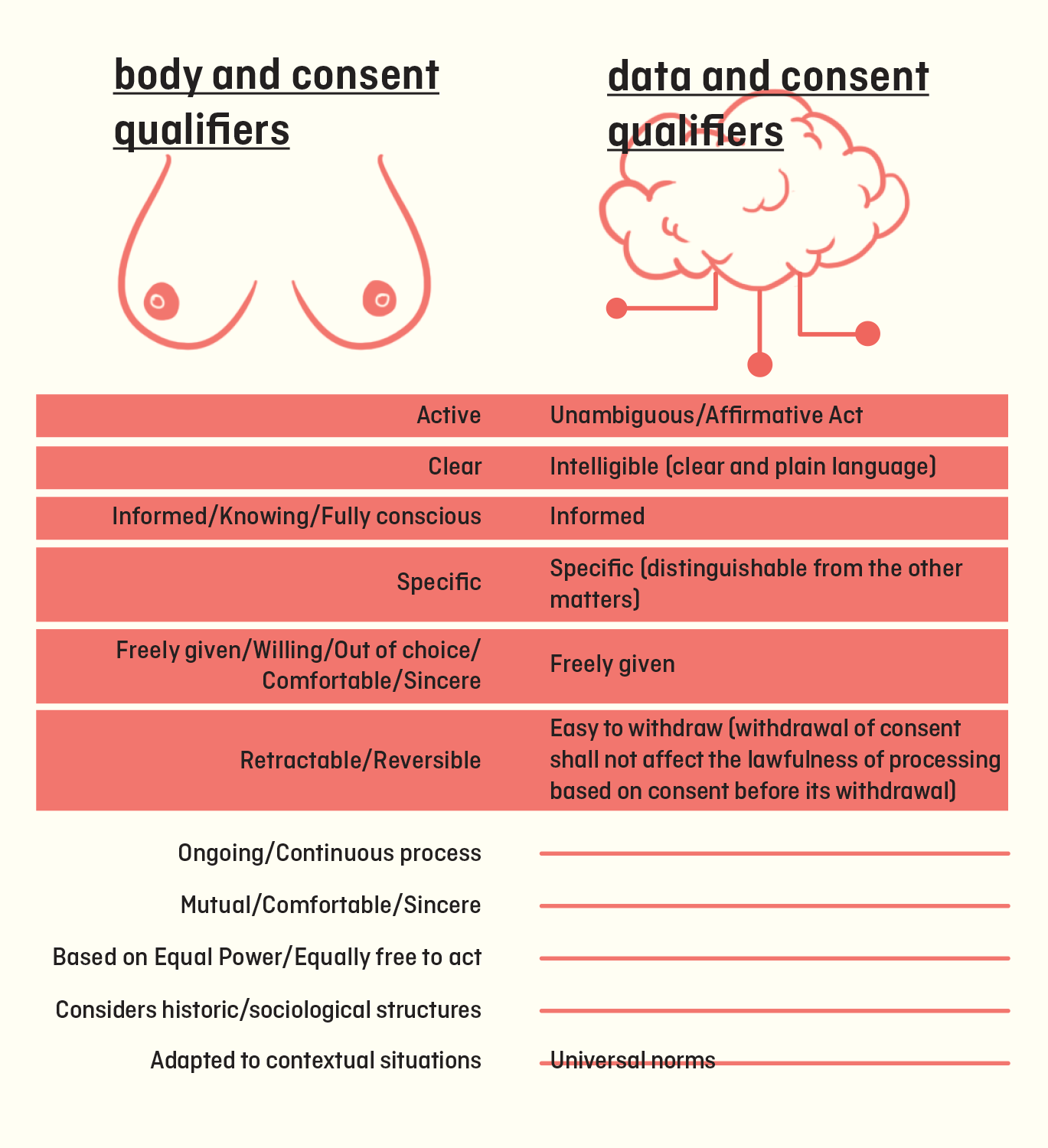

¿Que se han dado cuenta con el escándalo de Cambridge Analytica que explotamos sin permiso sus datos personales para venderlos a quien se nos plante y perfilarlos, clasificarlos y valorarlos sin ninguna transparencia? Ups, que ahora van a tener más botones de control de privacidad y asunto resuelto.

Los add-ons son el costo colateral con los que Silicon Valley trabaja: como Joi Ito dice en una de sus charlas Ted, en el vértigo de las tecnologías digitales del “despliega o muere” (deploy or die), no hay espacio para la reflexión crítica sobre los efectos de esas tecnologías desplegadas. Para Ito, las tecnologías digitales son la visión personal de un individuo emprendedor, aquí y ahora, no la consecuencia de una reflexión de una comunidad diversa.

Lo mismo ocurre con la violencia de género. Todos los escuetos avances que se han logrado con las plataformas son en forma de add-on.

Y QUE NO QUEDEN DUDAS. Que si hoy las grandes plataformas respondan en algo a actos de violencia de género, es solo gracias a la presión de las comunidades de feministas organizadas. Ha sido una lucha de años, de un nivel de desigualdad tremendo, con un abandono completo por parte de los Estados, para lograr que las plataformas transnacionales atiendan en un porcentaje mínimo las necesidades de las personas víctimas de nuestro continente.

Pero ocurre que, en un mundo de adds-on -donde pronto inventarán uno para saber si un donante se reformó o no de ser un predador sexual y, ¡santo remedio!– a veces el elefante enciende todas las luces y es simplemente imposible no verlo en cualquier sala.

El escándalo MIT Media Lab / Epstein que, por lo demás, será muy pronto olvidado, a, al menos, lanzado unos rayos de claridad para hacer esta pequeña presentación hoy sobre los desafíos de la violencia de género online en Chile y, me atrevo, en muchos otros países de América Latina:

- Sí, necesitamos políticas públicas que, más allá del punitivismo penal, se conecten con la amplia agenda de derechos de las mujeres y de género para comprender mejor el fenómeno y trabajar en distintas dimensiones un problema altamente complejo, que ataca muy diversamente dependiendo del punto de vista interseccional.

- Sí, necesitamos una mirada de derechos humanos a la violencia de genero online, tanto al comprender su daño, como al pensar en respuestas que, por ejemplo, no afecten a un vector fundamental de la libertad de expresión como es el anonimato.

Y sí, estamos en un sistema patriarcal que ya es de facto una imposición violenta, donde la “violencia de género” no es una excepción a la regla. Cómo no reconocerlo, si el caso Epstein-MIT Media Lab es una muestra más de que hay cuerpos que no importan.

Por eso hay que rescatar la potencia creativa y emancipatoria del feminismo para pensar y desarrollar una tecnología digital distinta y colectiva. No necesitamos necesariamente más mujeres, necesitamos más feminismo en la tecnología. Necesitamos una tecnología que deje de descansar, como si nada, sobre la destrucción de cuerpos que no importan, como podrían ser los de bio mujeres y niñas, queers y trans.

Escándalo tras escándalo, el poder de vender espejitos de la industria cultural de Silicon Valley es cada vez menos eficaz. En ese vacío creciente, hay una latencia que puede ser pura creatividad para construir tecnologías digitales y usos emancipatorios que, de verdad, enfrenten la misoginia y el odio con el fragor del feminismo del sur.

Muchas gracias.

:::::

*Texto escrito a propósito del conversatorio “Violencia de género en línea: diagnóstico y desafíos”