Techniques – Cutting 135 Degree Dovetails

Originally written May 2, 2018

I couldn't find anyone describing how to cut dovetails for non-square corners, so I decided to write this up. This trick will work for any angle dovetails, but you'll have to change up the workholding jigs.

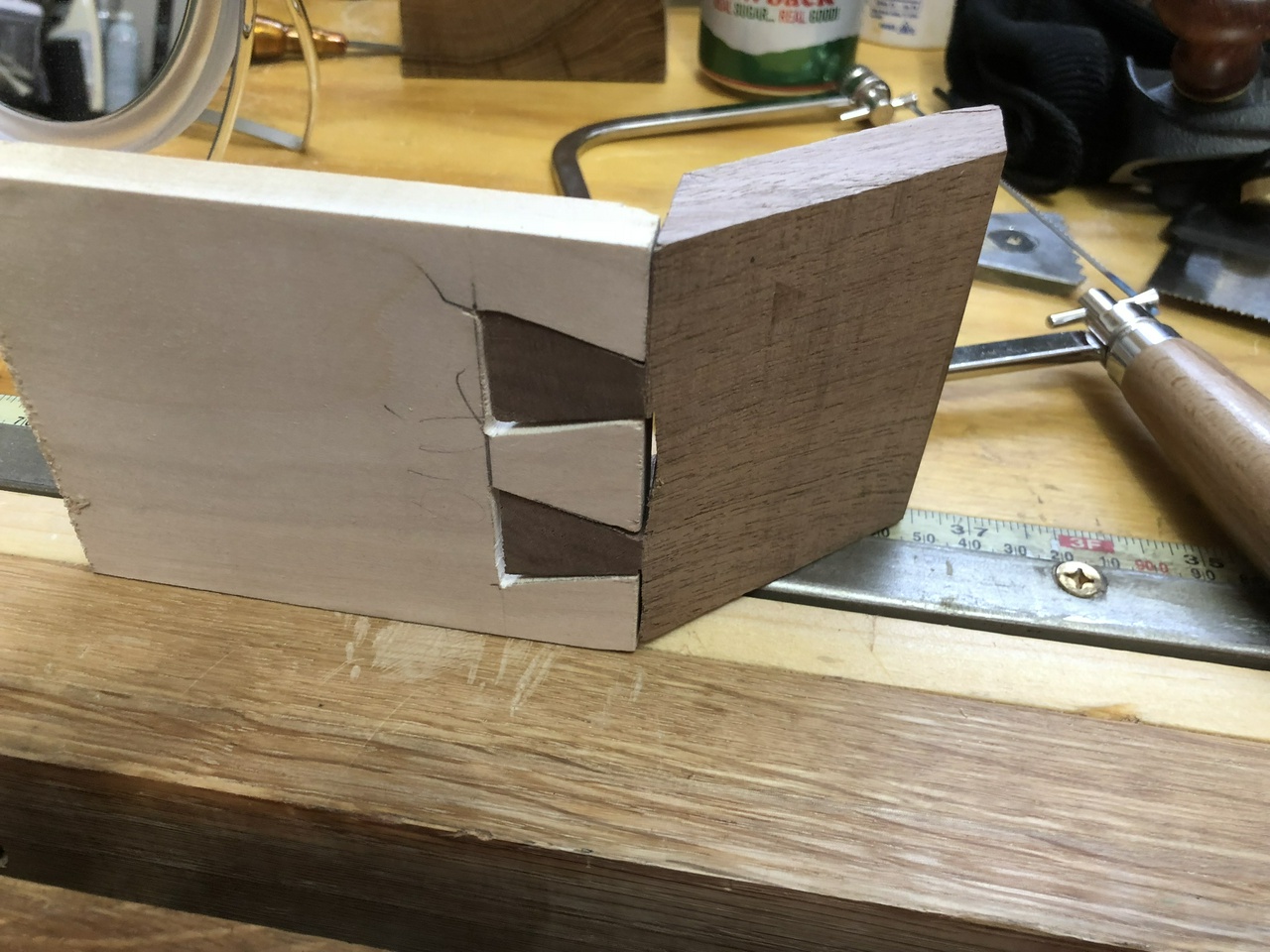

This is a description of how to cut dovetails for a 135 degree corner. This is the angle used on an octagonal box (if all the angles are equal). They're not perfect, and there's probably a better way to do it, but this is the best I found.

My first try cutting 135 degree dovetails used no special workholding. I just threw the pieces in the vise and started cutting. I cut tails first and I cut them pretty much as normal, except with the end of the board at a 45 degree angle, so they were pretty easy.

The pins were fairly straight too. This is feeling easy!

But the fit left something to be desired.

So I sat and thought for a bit and decided that maybe I could use a square piece in the corner, all tails, and put pins on the edge pieces that would go into it, and then cut the 45 degree angle afterwards. It couldn't be any worse than the previous attempt, could it?

Well, that worked okay, and I might end up trying that method again, but I'll have to think harder about the grain direction in that corner piece when I do.

So I tried again. Third time's the charm, right?

I cut the tails square this time, just like you would on a normal dovetail. I even gang-cut them two at a time.

Then I cut the pins on a board with the end angled 45 degrees using a jig I made for the purpose. I made the 45 degree end on the board using a miter jack before cutting.

Those came out pretty good I think. They're a little gappy where I went astray with the coping saw while cutting out the waste, but they glued up solid.

Hopefully someone else will learn from this and find it useful. To get the boards to look good in the corner, just make the corner piece (the walnut in the above photo) 0.7 times as thick as the edge piece (the ash). The example I show has the walnut thicker, and the corner looks kinda goofy to my eye.

#technique #woodworking #dovetails

Discuss... Reply to this in the fediverse: @davepolaschek@writing.exchange