Over time, wooden planes wear unevenly. Rookies to using them will tend to take a heavy cut at the start and end of a pass, which will tend to leave the bottom of the plane somewhat convex (which means no matter how you adjust it, the plane will be more aggressive than it should be). And just normal use will tend to make a plane slightly concave (which will mean no cut at all until the plane is set very aggressively, or unless you push down hard enough to flatten the plane out a bit).

In either case, the first thing you need to do is get the length of the plane flat. If everything else is right with the planes, you can use the hollow to flatten the round, and vice-versa. It's best to try and get the round close first, as this can be done with a bench plane if need be (you'll get a faceted bottom curve, but that's easily corrected).

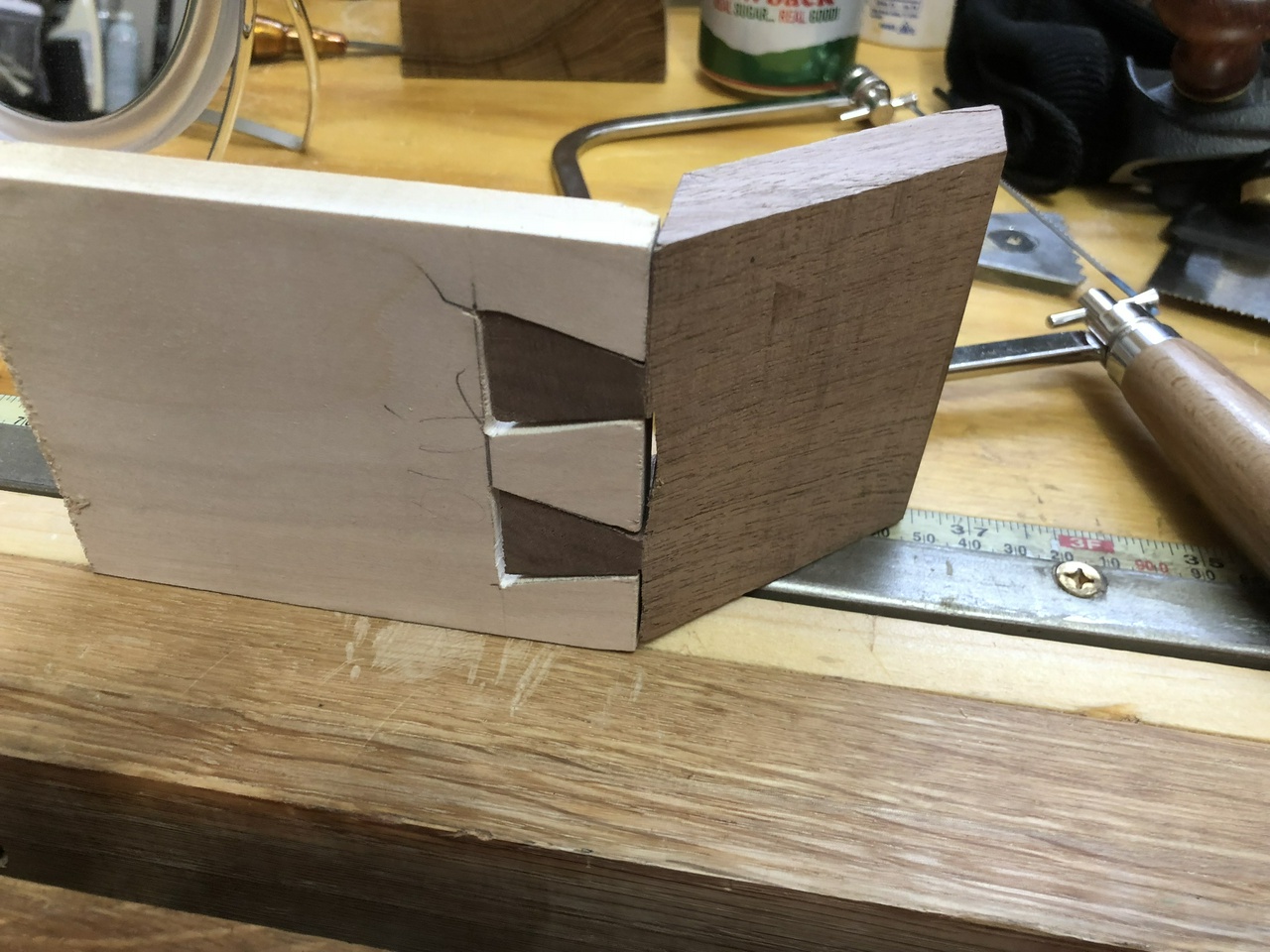

If you have a convex plane, mount it in your bench vise, sole up, with the iron set in the plane, but retracted enough that it won't cut. Use the matched plane to take shallow cuts off the middle, planing from toe to heel. If the planes aren't matched, this will begin to match them.

If you have a concave plane, concentrate on the ends of the plane. It shouldn't take more than three or four passes unless your plane is way out of shape.

If you had corrected a round with a bench-plane, use the hollow and roll it slightly side to side to knock off the facets from that process to make a nice smooth curve.

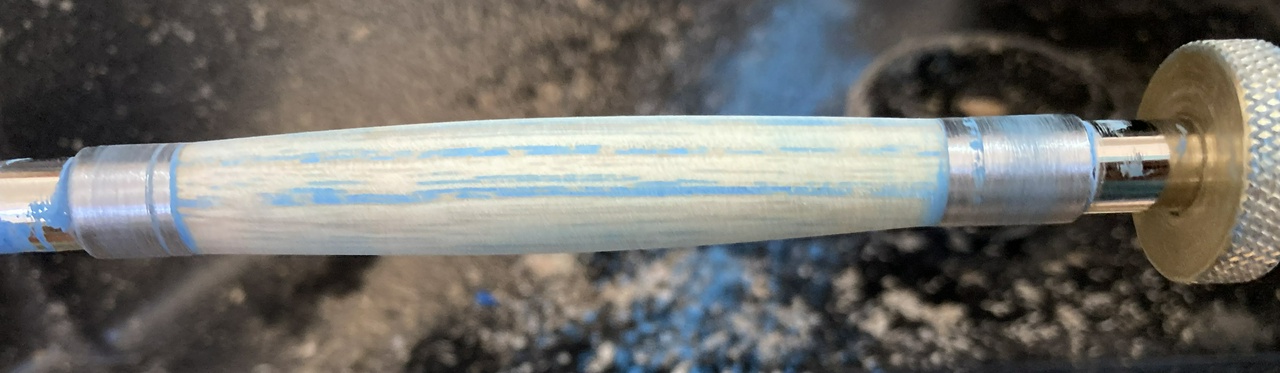

After a few passes, retract the blade for the matched plane, set the wedge again, and wrap the bottom with some sandpaper (120 grit has been a good starting point for me) and sand to get the plane bottom correct.

The important thing is to set the blade in the plane body before adjusting it so the plane won't be warped from its normal use-state. This applies to both the plane you're reshaping as well as the plane you're using to reshape the other.

If the curve of the plane is off (they seldom are by much), simply rotating the other plane while leveling the length of the bottom will get you closer to correct, since the curves are circles.

Once you have one plane (probably the round) good, change them around, and mount the hollow in the vise, and flatten its length similarly, first with the plane, and then with sandpaper.

To check the curve on the plane (once the length is flat), I use an auger bit of the appropriate diameter to compare against the hollow. My good augers will give me a pretty good idea if the curve is wrong on the hollow. If it is, I will mark the high spots with a pencil, then use the matching round to plane off the high spots. Once the hollow is correct (according to the auger bit), I use it to make sure the round has the correct curve. Small adjustments here! It's highly unlikely the curve of the plane sole will be too far out of whack, unless you're changing it (which is more advanced than I'm covering here). More likely is a small ding in the sole that you can usually ignore unless it's too near the mouth.

With the wood correct on both planes, it's time to start sharpening the blades. I have a couple synthetic stones that I got from Razor Edge Systems which don't require lubricant. I keep them flat with a diamond plate, and the coarse stone works well for establishing bevels and making sure the back of a plane blade is flat. For the hollow blades, I use slip stones.

For a hollow or round, you want to do about 60% of the work on the back of the blade. This is pretty easy, since you're just making sure it's flat. Don't do “the ruler trick” or lift the tang of the blade, just make it flat on the stone.

For the bevel, I start with a known-good plane body (see above) and use a marking knife and layout fluid to paint the face of the blade, and then mark the correct curve on it. If the blade is WAY out of shape, I'll take it to the grinder and grind to that curve 90 degrees from the back, and then grind the bevel by hand, but I've only needed to do that on about one blade out of ten.

Other than that, it's just sharpening. Just make sure to establish the correct curve first, then worry about the bevel. And try not to use the same track on the stone every time so you have to flatten your stone more often. About 30 degrees will be fine for the bevel in almost all cases. If you have a hollow-ground bevel (from a grinder), you'll want to lift the tang of the blade just a hair while sharpening the bevel because that's the way the geometry works. Matt Bickford's book (see below) has pictures and an explanation.

Once the blade is sharp, use a strop to keep it touched up. I've got a set of hollows and rounds that I'm slowly getting back in service using these methods, and I haven't had to sharpen the blade on any of them a second time yet. But every time I use one, I'll give its blade a couple passes on the strop just to make sure the edge stays nice and sharp. And it gives me practice adjusting the blades so I get better at that.

And if you're serious about this, buy a copy of Matt Bickford's Mouldings in Practice and read chapter 14 of that book. It's a much better treatise on maintaining hollows and rounds from a guy who has a ton more experience at it than I do.

Edited to add: my buddy Kent found a three-video series for those who learn better from videos than from words.

Techniques Contents

#woodworking #mouldingPlanes #maintenance #technique

Discuss...

Reply to this in the fediverse: @davepolaschek@writing.exchange