Small Veneered Box

I’m going to be making a new top for our dining room table one of these years, and as that will be a 5 foot diameter circle of plywood, veneered and edge-banded, I figured I should practice veneering a bit.

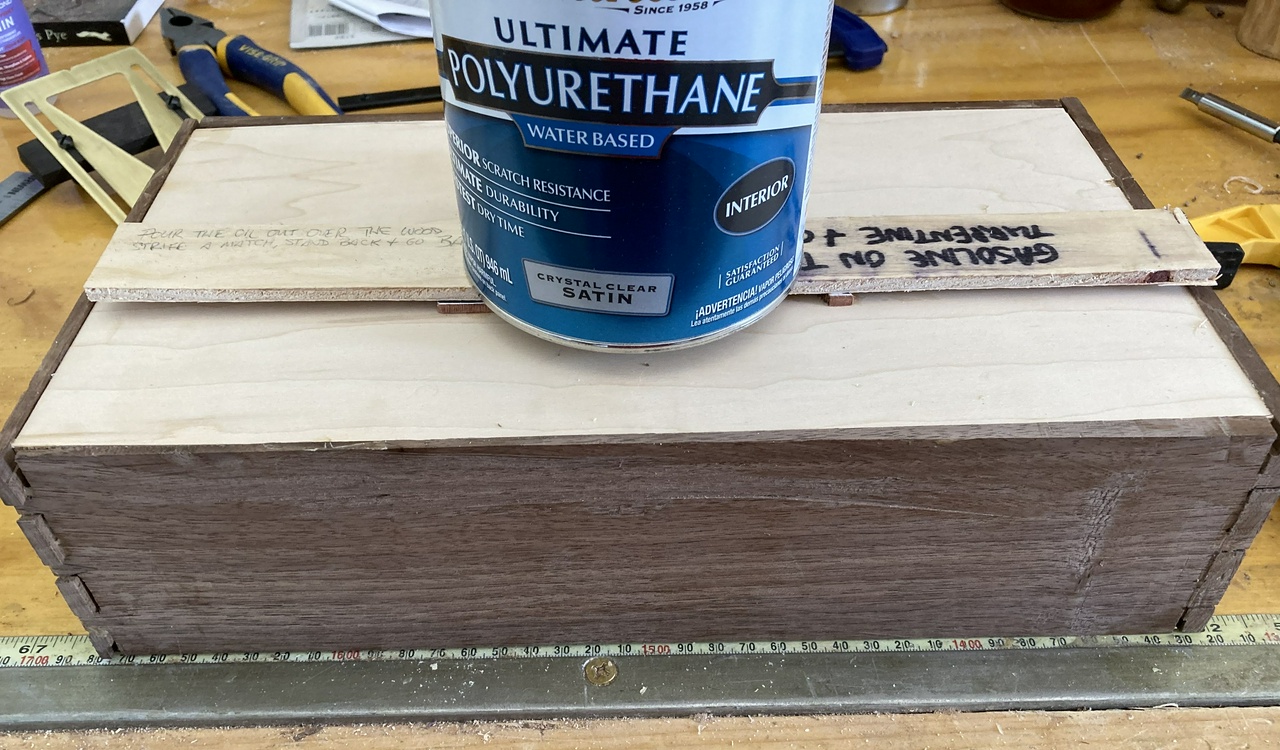

I found a small pine box with no bottom or top (I think it was the excess trimmed off a box to hold one of my lathe chucks) which was slightly under 6 inches square, by about 2½ inches tall. And I found some 6 inch wide hardwood “micro lumber” which was ⅛ inch thick that I used to make a top and bottom for the box. They’re simply glued on.

While that was drying in the clamps, I dug through my veneer sampler box that I bought from Veneer Supplies (mine was an 8½ x 11 x 6 inch box) and found a sheet of lacewood or snakewood which should be big enough (it’s 8 inches by 10½ inches) to cover all four sides of the box.

Next up will be softening and flattening that sheet (I think I’ll use a couple pieces of picture framing acrylic and a stack of wood for a press), mixing up a new batch of glue, and cutting the sheet into four pieces the right size for the sides of the box.

We’ll see how it goes!

That answers part of the question. I definitely need to treat the cauls I use so the glue that seeps through the veneer doesn’t stick to them.

I’ve stuck a piece of packing tape on each caul, and did the other two sides of the box. If that works, I’ll remove the damaged side and find another piece of veneer in the sampler box to try.

With fresher glue today, I also had to thin it a bit more so I had a decent working time. By the time I got all the clamps on the box, this had happened:

So I soaked that side of the box down again, and used a card scraper to gently peel up the veneer, scrape off the glue, put on new glue, and try again. I can see that my strategy of leaving the veneer overlarge and trimming it back to the box dimensions after the glue has dried won’t work, so I learned at least two things this morning.

But I think that’s it for today. I’ll maybe look for a piece of veneer for the badly damaged side and cut it to size, but I need to let the box dry before trying to do anything more with it.

After a few days of no shop time, I got back out to the shop this morning (Saturday, the 17th). I planed the wrecked veneer off the side of the box using my Carter mitre plane, then found a piece of birch burl which I thought would look nice and glued that on.

When I removed the box from the clamps and cauls after a half-hour, the new veneer looked good, so I set it on the bench to finish drying while I worked on some other things. After a half-hour, I noticed the burl veneer had curled almost into a circle as the side not glued to the box had dried faster than the side next to the box. I didn't take a photo, but I basically wet everything down and re-glued the veneer down. Hide glue was invaluable here, since hide glue will stick to dried hide-glue. PVA glues would have required completely removing the veneer and sanding the underlying pine clean, since almost nothing will stick to dried PVA glue.

With the burl glued on, and given a couple hours to cure, I pulled the box from the clamps again, and proceeded to trim the edges of the burl veneer. I used one of my gent saws with the finest teeth (32 tpi, I believe) to cut as close to the edge of the box as possible, then used the mitre plane to get the edges baby-butt-smooth, and hit the box with a coat of tung oil. The result is above.

The next session in the shop, I'll cut this box open, add hinges and a latch, and do some serious finishing. I think I'll probably French polish the box.

I cut the box open and put in an ash liner, which serves to align the top, and hold it in place. I decided against hinges and a latch, preferring a piston fit.

The ash liner needed some reinforcement at the corners, so I cut some spalted elm into triangular shapes and glued it in the corners. More visual interest, and much-needed reinforcement.

I also added some edge-banding to the top and bottom surfaces that were exposed when I cut the box open. This makes the box look much more finished. I should have been more careful about trimming the inner edges of the banding for a better look, but had the edges been all the same size, I would not have needed to do the trimming. I also didn’t have quite enough of one of the styles of banding to go all the way around the box, so one side got a different pattern. It looks a little goofy, but again, more practice!

And then I started French polishing, but at some point the already-applied finish pulled a bit (I probably did not have enough oil on my pad) and left a bit of a mess, so I sanded the box back a little bit with 0000 steel wool and started applying Tried and True Varnish Oil, which will be my final finish. It’s nearly fool-proof, though a bit slow, as each coat needs to dry overnight before the next coat can be applied, but it’s simpler to apply, and looks really good once enough thin coats are built up.

A think a few more days of this slow finishing regimen will see the box complete. At that point I’ll give it a few days to cure, and then apply a coat of paste wax. I’m not sure what I’ll do with the box, but I suspect it will get given away.

#projects #veneering #buildBlog

Discuss... Reply to this in the fediverse: @davepolaschek@writing.exchange