by Darius Kazemi, Jan 1 2019

I'm reading one RFC a day in chronological order starting from the very first one. More on this project here. There is a table of contents for all my RFC posts.

This post is probably going to be one of my longest because I need to set the historical context for RFCs in addition to talking about the actual RFC so, here we go!

Setting the stage

ARPANET was the precursor to the internet. I'm not going to go into the full history of the ARPANET but the original concept before it was even known as ARPANET was to have a redundant, decentralized communication network for the military and the government that could survive a nuclear attack since it didn't have a single point of failure. There was a proposal for a nameless, nuclear-survivable voice communication network that was published in 1964 by RAND Corporation, an extremely influential post-WWII American think tank that to this day is under-documented in terms of its influence (but here's a decent summary).

But it was mostly a proposal that was batted around, garnering small contracts here and there, until finally in June 1968 the real funding kicked in and work began in earnest. The ARPANET project resulted in the invention of TCP/IP and packet-switching, two absolutely fundamental internet technologies. For much of its early existence it connected a very specific slice of the United States: top tier research universities, US military research facilities, and various private defense contractors.

It was this round of 1968 funding that kicked off a whole bunch of events, including a series of meetings that would eventually be called the Network Working Group. A young grad student at UCLA named Steve Crocker had been attending meetings. He was the junior member of this group (only 25 at the time), which included Steve Carr, from University of Utah, and Jeff Rulifson and Bill Duvall from Stanford Research Institute.

Crocker, being such a junior member of the group, decided that one of the best ways he could contribute was to take meeting minutes. Like, maybe they shouldn't be just leaving random notes on blackboards and in people's short term memories, you know? So in April 1969, less than a year after the first Network Working Group meetings, he did just that. RFC 1 is the meeting minutes for a meeting as recorded by Crocker.

The technical content

Titled “Host Software”, RFC 1 lays out the handshake protocol for hosts (servers) to talk to other hosts. Keep in mind that nothing here necessarily describes how this stuff was eventually implemented. This was all just a plan for implementation!

Message headers and network topology

So in the parlance of the ARPANET, hosts are basically what we would consider servers today. It's the computer with a person on the other end that is either sending or receiving data and doing something with it. The proposal here is that messages between hosts are transmitted with a 16-bit header. 5 bits are reserved for the stating which host the message is to be delivered to. (This means they only planned for 32 interconnected servers at this point!)

1 bit was reserved for tracking information. That's right, they had plans for analytics as far back as 1969, which makes sense: no way to tell if this wacky networking concept even works if you can't measure it working. The bit said “this is a 'real' message that should be tracked by the Network Measurement Center at UCLA”. If the bit was not set then I'm guessing it was a measurement or some kind of meta message that wasn't supposed to be counted in their actual experiments.

To understand the next part of the header you should understand that the network was set up as a host (server) that talked to an IMP (an Interface Message Processor, basically what we'd call a router today), which communicated via a bundle of 32 links with another IMP connected to its host.

Network congestion was an extremely serious problem given the limited technology at the time, so a full 8 bits of the header are reserved for encoding information that was meant to mitigate this. Links are, basically, the communication highway that connects one host to another via its IMP router-like-thingy. Every pair of hosts is connected by “32 logical full-duplex connections over which messages may be passed in either direction”. In simple terms it means that any two servers could have 32 separate simultaneous streams of 0's and 1's passing back and forth. Each of these streams is a link, and they are numbered 0 to 31. However, according to the document, the IMPs couldn't handle 32 simultaneous connections and it was up to everyone on the network to be a good samaritan and not basically commit the 1969 version of a denial-of-service attack. My best reading of it is that these 8 bits are a way for a host to say “hey I'm using this small portion of the 32 channels right now, please don't use my channels and cause a collision, try using a different set of channels”! The 8 bits were proposed to be used at least in part to describe which of the 32 links between these IMPs should be used for a particular message. (I guess it's fortunate that they only planned for 32 servers. It would be trivial to just reserve one link channel for every host and call it a day. Private highways for everyone!)

Software requirements

They were keenly aware that people aren't going to adopt a new technology if it doesn't fit with their existing workflows. A section of the document called “Some Requirements Upon the Host-to-Host Software” states that they pretty much need to simulate a teletype interface. A teletype, or teleprinter is basically a typewriter hooked up to a phone line and not only could you type on it to send messages, but it could receive messages and type back at you, which was how you knew what the computer's output was. It was the main way people interacted with computers before computer monitors were affordable to build. Monitors were becoming more and more common by 1969 but teletype was still dominant tech that everyone knew how to use.

There's also a note about error checking. In addition to checking for errors between hosts, they also note that they'd like to see error checking between hosts and routers. There's a droll aside here:

(BB&N claims the HOST-IMP hardware will be as reliable as the internal registers of the HOST. We believe them, but we still want the error checking.)

BB&N, or BBN as it's now known, was and is an R&D company in New England. They were not as large as defense contractors like Raytheon (which now owns them) but were widely known for their work in acoustics, and defense contracts were a big part of their business. I spoke via email to Dave Walden, who worked at BB&N from 1967 to 1995, who says that by 1969 BB&N had about 800 employees and the revenue approximately half R&D/consulting business and half from products or paid services like their TELCOMP time sharing software. They were instrumental in ARPANET, and of course they made claims the communication between the server and the router (in modern terms) would be as error free as the communication on the circuits the server uses to talk to itself! Big talk from our New England eggheads.

The actual software

This lays out the basics of a handshake between two computers. It says that link 0 is reserved for initial handshaking, which is when one computer says “hey I want to talk to you” and the other computer says back “okay I am listening”. This is how the first computer knows it can start sending data.

Interestingly they also propose a special mode for “high volume transmission”, basically for sending large data files. The problem with big blobs of data is, well, what if your big blob of data happens to have the special code that normally means “drop this connection” in it? We have to be able to say “hey for the next little while, just ignore any weird messages you get and please assume everything is pure data.” This is still a problem we contend with today in many different computing contexts, and it's still incredibly annoying.

They're also concerned with latency. Specifically they call out Doug Englebart's console at Stanford Research Institute as an extra sophisticated and highly interactive computer that needed a low latency connection: this completely makes sense since by 1969 Englebart had already invented the computer mouse and was doing graphical computing with it!

They also discuss the Decode-Encode Language, DEL, which is super cool but I'll get to that in my post on RFC-5 in... four days. Jeez. What did I sign myself up for here.

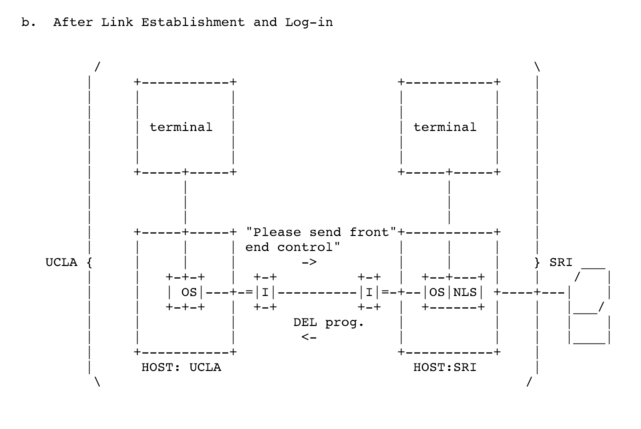

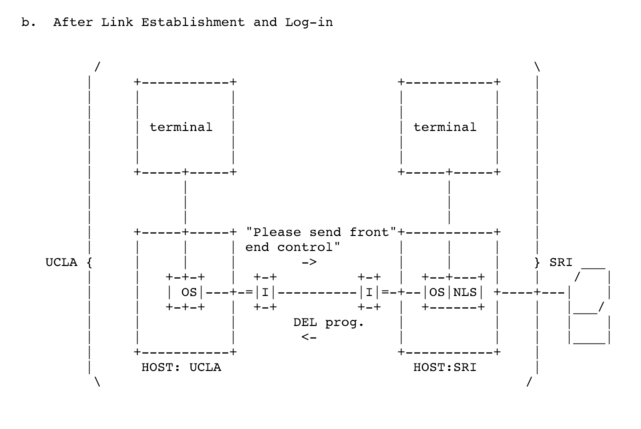

Oh also I hope you like... well maybe it's not ASCII art but it was definitely typewriter art. There is some good-ass typewriter art in this document: (see edits below)

There are some diagrams in the RFC that were almost certainly hand-drawn in the originals but were updated to ASCII art in 1999 when these were transcribed for posterity by the IETF:

(Okay, editing to add a brief aside: it's unclear if this art was in the original typewriter document as laid out or if the original document had inline hand-drawn diagrams. This document was translated to electronic form in 1997 and this diagram absolutely has the feel of a 90's textfile diagram. I'm actually more and more certain that this was hand drawn and the typewriter art was introduced in 1997 but I can't find scans of the original RFC. If you know how to find them, please let me know!!)

(Second edit: I haven't found scans of this document yet BUT there are scans of RFCs from just a month later like RFC-9 and the diagrams in these documents are hand-drawn as I suspected.)

(Third edit, Jan 23 2019: there are now scans at the Computer History Museum! Turns out they were beautiful hand-drawn diagrams. More info here.)

In the diagram you can see two hosts and their IMPs (labeled “I”). “NLS” over at the Stanford Research Institute node is Englebart's graphical computing system that you could tell they were practically drooling over.

Another super cool thing implied here is that these are all basically running their own home made operating systems. So this isn't like two Windows machines talking to each other. This is cross-platform communication.

General analysis

If you're familiar with RFCs you might think of them as standardization documents, and that is in part what they serve as today (it's more complex than that, many modern RFCs are categorized as “Experimental” or “Informational”). But back in 1969 RFCs were much more like speculative proposals, the kind of thing you might make an internal wiki page for in a project in a modern office. “Hey everyone, I had this idea to solve this engineering problem so I wrote this document, what do you think?”

The document's four paragraph long introduction concludes:

I present here some of the tentative agreements reached and some of the open questions encountered. Very little of what is here is firm and reactions are expected.

As implied by its name, the request for comment is a humble request, not an ultimatum.

Also of note: this thing is REALLY WELL WRITTEN. The language is very easy to understand and I'm in awe that 25 year old Crocker could write so clearly about extremely complex technology that didn't even exist yet. No wonder this kicked off a tradition of technical writing that would last literally half a century.

More reading

This blog post from Sam Schlinkert was a valuable resource in writing this post, as was ICANNWiki. You might want to read the book Sam is summarizing in his post, Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet, by Katie Hafner.

The Internet Society has a detailed history of ARPANET and the multiple streams of work that converged over the mid-1960s from researchers working independently on these ideas.

How to follow this blog

You can subscribe to its RSS feed or if you're on a federated ActivityPub social network like Mastodon or Pleroma you can search for the user “@365-rfcs@write.as” and follow it there.

About me

I'm Darius Kazemi. I'm a Mozilla Fellow and I do a lot of work on the decentralized web with both ActivityPub and the Dat Project.